In a scathing investigatory report released last week, Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred repeatedly refers to the Houston Astros’ sign-stealing scheme in 2017 and 2018 as “player-driven.” Yet Manfred also declared: “I will not assess discipline against individual Astros players.”

So while Manfred suspended Houston general manager Jeff Luhnow and field manager A.J. Hinch for the 2020 season—

they were later fired—no active players were even named for their involvement. Manfred justified that decision by saying it would have been “difficult and impractical” to punish players, given that virtually all of them had knowledge of or were involved in the operation to use technology to illicitly obtain and relay opposing catchers’ signals.

But there is a simpler explanation for why no players were penalized: The league and the MLB Players Association struck an agreement early in the process that granted immunity in exchange for honest testimony, according to several people familiar with the matter.

The league was quick to make such an offer, these people said, in part because it did not believe it would win subsequent grievances with any players it attempted to discipline. That’s partly because of a bureaucratic shortcoming: The Astros’ front office never discussed with players the league’s admonitions against using electronic devices to steal signs, according to Manfred’s statement.

The deal is a sign of MLB’s desire for a speedy and conflict-free investigation, the continuing power of the baseball players’ union and the fragile state of the sport’s labor relations. The promise of amnesty allowed the league to interview 23 current and former Astros players during the two-month investigation.

The result is a situation that led to the harshest penalties in recent baseball history—none of them directed at the people Manfred said actually committed the offense. That has attracted public criticism even from some players who are members of the union.

The nature of the Astros’ sign-stealing operation became public in a Nov. 12 story published by The Athletic, prompting MLB to launch a formal inquiry. But the genesis of the pact between the league and the MLBPA goes back to Sept. 15, 2017, when Manfred announced that he had fined the Boston Red Sox for transmitting signs from their replay review room to individuals in the dugout wearing smartwatches.

That same day, Manfred issued a memo to all teams reiterating that using electronic equipment to steal signs was a violation of league rules and that future transgressions would be met with severe discipline. He specifically said that GMs and managers would be held accountable for the conduct of their charges. Another memo sent out in March 2018, attributed to chief baseball officer Joe Torre, expanded on the prohibition.

Manfred said that despite receiving those memos, Luhnow never forwarded them to or addressed their contents with the players and field staff, nor did he “confirm that the players and field staff were in compliance with MLB rules and the memoranda.” Through a spokesman, Luhnow declined to comment.

This was an important fact for MLB if it had wanted to try to discipline players. Penalties would have been met with grievances by the MLBPA—grievances that the league believes it would have lost, people familiar with the matter said.

After all, Manfred said, Hinch knew the sign-stealing was going on and didn’t stop it. Bench coach

Alex Cora was an active participant in the plots. So was outfielder

Carlos Beltrán, a respected veteran. Therefore, the union could have successfully argued in a grievance hearing that the players didn’t know they were in the wrong, since their superiors never directly informed them and even appeared to condone their behavior. (Cora and Beltrán both lost their jobs last week as the manager of the Red Sox and New York Mets, respectively.)

MLB wanted to avoid grievances altogether because of how they would have hindered the investigation. Under the collective bargaining agreement, the MLBPA couldn’t stop MLB from interviewing players in relation to the case. But the union could exert some influence on the scheduling of those interviews, potentially grounding the entire investigation to a halt.

Once the parties did talk, players might not have been forthright in their responses if they feared repercussions that would impact their earnings or playing status. Almost no active players, for instance, cooperated with the Mitchell Report, which looked into the prevalence of performance-enhancing drugs in baseball. That investigation took 20 months before its release in 2007. Because players spoke freely this time, MLB wrapped up its dive into the Astros and took decisive action in two months.

A person familiar with the matter said that MLB determined quickly that it didn’t intend to pursue suspensions for active players. One reason for that, this person said, was MLB’s belief that it would be inappropriate to punish teams who have since acquired players who played on the 2017 Astros. For example, the Minnesota Twins had nothing to do with what the Astros did, so why should their championship aspirations potentially be derailed because they signed Marwin González last winter? (Limiting discipline only to players still on the Astros would’ve been a nonstarter in a grievance.)

With suspensions off the table, it became clear that it would benefit the investigation, the league and the union to simply focus on arriving at the truth. There were no intense negotiations; the league offered immunity essentially from the outset. The same rules will apply to the ongoing investigation into the Red Sox, who have been accused of illegally stealing signs during their run to a World Series title in 2018, with Cora as their manager.

By working with the MLBPA on this issue, MLB avoided sparking another fight in what has been a contentious period between the league and the union. The slow pace of the free-agent markets after the 2017 and 2018 seasons caused massive outcry by the players and their representatives, sinking baseball’s labor relations to their lowest point since the strike of 1994.

Though this off-season has seen a more robust employment market, tensions remain high as the two sides prepare for what is expected to be a tough CBA negotiation after the 2021 campaign.

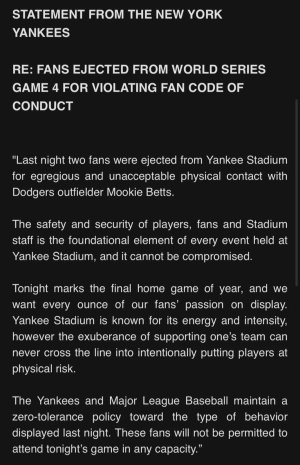

It appears not every player agrees with that course of action. Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Alex Wood said on Twitter: “The fact that there hasn’t been any consequences to any players up to this point is wild.” Other players have expressed similar discontent.

Union officials recognize players are emotional about this issue, especially the Dodgers: They lost in the World Series to the

Astros in 2017 and then to

the Red Sox in 2018. Those who weren’t part of the investigation weren’t told that players were granted immunity.

That might not be the case if this form of cheating continues to be an issue moving forward. MLB expects to unveil a revised policy designed to combat technology-assisted sign-stealing before opening day, following negotiations with the MLBPA. It could include agreed-upon penalties for players in the future.