Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Official 2023 Chicago Cubs Season Thread Vol: (17-17)

- Thread in 'Sports & Training' Thread starter Started by CP1708,

- Start date

Lake Shore Drive

formerly slp product

- Feb 8, 2005

- 7,336

- 2,445

Why????

He was pretty decent this year, 15-10.

Wonder who gets the spot Montgomery? Maybe CJ??

Either way Cubs unload 10M off the books.

I'm sure Theo and Jed got something planned out.

- Jun 26, 2009

- 9,064

- 1,157

Losing Fowler would be huge but I think you gotta let Almora develop.

I don't want Chapman. I'd rather sign Jansen.

I don't want Chapman. I'd rather sign Jansen.

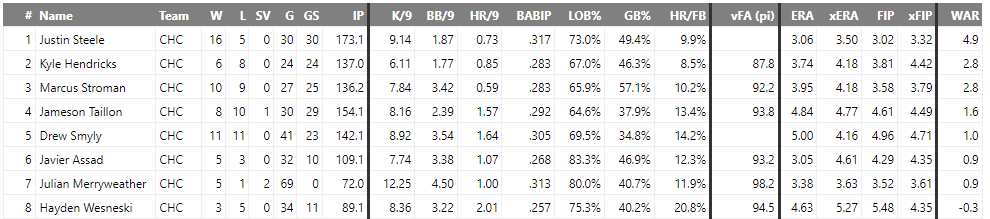

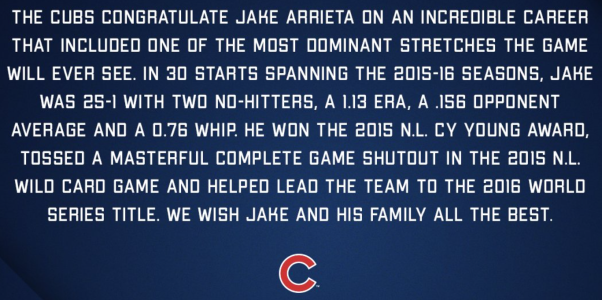

It must be noted, however, that health isn’t the only relevant factor. It’s a bit gauche to critique the newest champs while the Champagne is still drying, so I ask your forgiveness in advance. With Hammel gone, here are the returning four members of the Cubs’ rotation: John Lackey, Jon Lester, Jake Arrieta, and Kyle Hendricks. Now here are their respective ages on Opening Day 2017: 38, 33, 31, 27. Lackey is in the final year of his contract, battled a shoulder injury this season, and was good, not great, this season. Lester has been fantastic for the Cubs, but considering that they have him under contract through age 36 or 37, aging-induced decline is a matter of when, not if. Arrieta returned to Earth this year after his phenomenal 2015 season. But, hey, at least there’s Kyle Hendricks.

The Cubs’ rotation is talented and there’s no compelling reason to think they won’t be fine in the short-term, but it must be acknowledged that, for the most part, their peak is behind them. This, of course, stands in stark contrast to their almost obnoxiously young and uber-talented lineup. It is now the responsibility of the Cubs’ front office to find ways to maximize the team’s long-term success as this young position-player core continues to grow at the major-league level. This will have to mean finding ways to replenish their rotation talent as time wears on and a natural starting point to begin that turnover was by saying goodbye a 34-year-old fifth starter who is battling an elbow injury. From that perspective, declining the Hammel’s option was a no-brainer.

Basically using 2017 as the season in which to try out 1-2-3 different starters to see if they can find more than 1 for 2018 and beyond. Had they kept Hammel, they would only have Lester and Hendricks for 2018 FOR SURE, and then 3 guesses for the rest. (I'm starting to believe that Arrieta may not be back in 201

They basically need to do it all over again with Arrieta/Hendricks, finding guys and getting them turned into great starters out of nowhere, so to speak.

Some of the stories will say that it had to happen that way — that for the long-accursed Cubs to take home a title would require a rain-delayed, one-run, extra-inning win in a seven-game World Series. That in the course of the four hours and 28 minutes it took for one team to screw up slightly more than the other, both managers would have to make inexplicable mistakes. That a hitter nicknamed “Hulk” would have to steal a base after reaching on an infield single. That a retiring team leader would have to go deep against the 6-foot-7 stopper who’d been almost unblemished in October before that inning began, and that a speedster who hadn’t homered since August would tie it with one in the eighth against a guy acquired months earlier with only that moment in mind. That another hitter, who’d already homered, would try to drop down a two-strike bunt in the ninth with the go-ahead run on third, foul it off, and scream in frustration. That two runs would score on a wild pitch, which followed three errors and a pickoff. That after all the twists and turns, the “This is overs” and “No it’s nots,” the heavens would have to open up after nine innings, with both teams’ odds of victory tied at precisely 50 percent. That when it finally, unfathomably ended, one of the worst hitters in history would have to make the last out.

The truth is, though, that it didn’t have to happen like this:

It could have been a blowout. It could have been a sweep. In Chicago, no one would have cared. After 108 years without a World Series win, Cubs fans would have taken any kind of title. Fluke team that rolls right through the playoffs after topping a terrible division with 83 wins, like the 2006 Cardinals? Sure. Shameless team that buys a title by outbidding the rest of baseball, then immediately resells its stars, like the 1997 Marlins? Not ideal, but beggars, choosers, etc. Team that wins only because its opponent throws the World Series, like the 1919 Reds? Whatever. Flags fly forever.

Cubs fans would have settled for a so-so wild-card winner that snuck into an unexciting World Series, and they would have happily accepted a victory over a team that snuck into the playoffs and limped to a pennant. Instead, they won 113 times en route to a sloppily glorious Game 7, in which players, managers, and umpires alike made mistake after mistake but most of the Cubs’ mistake-makers redeemed themselves. That 10-inning classic, whose never-again nuances should be dissected for days, backed up a comeback from a 3–1 World Series deficit, the first in more than 30 years. The Cubs took down the Cleveland Indians, the only other team with a title drought whose notoriety could come anywhere close to comparing to theirs, and they did it despite that team looking unbeatable against its first two playoff opponents. For a final challenge, Chicago faced Corey Kluber, Andrew Miller, and Cody Allen, the trio that had entered the game with a combined 0.61 postseason ERA. Kluber and Miller had allowed four runs in 47 1/3 playoff innings; the Cubs solved them for six in 6 1/3.

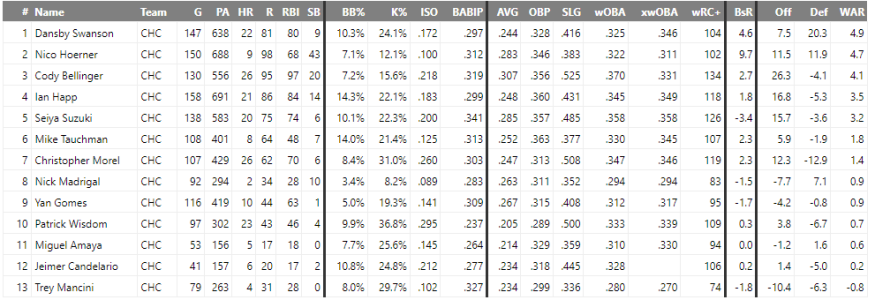

All of that small-sample intensity succeeded a six-month demonstration of the many ways in which a team can be good at baseball. The Cubs won with a club that was projected to be the best in the sport and still exceeded expectations (despite probably being unlucky). No team was better at hitting, and no team was better at run prevention. The Cubs even ranked among the best baserunning teams, as they reminded us in Game 7 with a Kris Bryant tag-up here and an Albert Almora tag-up there. You have to drill down to the level of individual pitch types to find something they didn’t do well.

If you like getting giddy at great results — sorting countless leaderboards and seeing the same name at the top — the Cubs were the team you obsessed over when you weren’t watching your own. If you prefer a sound process, the Cubs were your fantasy team too. Led by Theo Epstein, who’s earned a lifetime exemption from FCC fines, the Cubs took a truism known to every team — pitchers aren’t dependable — and instead of trying to win with attrition, made fungibility work in their favor. They drafted and developed more position players than they had places to put them, and they trusted in their smarts (and, OK, some cash) to fill out their staff with future Cy Young Award winners (Jake Arrieta; Kyle Hendricks?) who’d belonged to other teams. We can’t say they left nothing to chance, because it’s baseball — there’s always a lot left to chance. But they built a team too good for bad bounces alone to derail.

Now they have not only their first title in living memory, but something else almost as sweet: strong odds of adding a second (and, like the similarly slump-busting Red Sox, of not stopping there). The foundation of the 2016 team that slugged and stole and played unprecedented defense will be back and, if anything, better: Bryant, Addison Russell, Anthony Rizzo, Kyle Schwarber, Jorge Soler, Jason Heyward, Javy Báez, Willson Contreras, and Almora were all in their age-26 seasons or younger. The front-office essentials are signed to extensions, and the Cubs can afford to keep their young core in place. The aces are older, but the Cubs have unearthed new aces before.

This is the start of a run that might make us sick of the Cubs; with one win, their perpetual underdog status was stripped away, with no one on the North Side sorry to see one of the sport’s most lasting legacies go. For now, though, the Cubs’ charisma makes it easy to empathize; when they weren’t beating us, it was tempting to smile along.

Is there any way in which it could have been better? Maybe the Cubs could have won with a cleaner conscience. Epstein could have tried to assemble a superteam without first being bad on purpose, but the Cubs aren’t the only team that’s benefited from tanking. And they could have won with, oh, Henry Rowengartner coming in for the save in place of the pitcher they picked up at the trade deadline, who was suspended to start this season following domestic violence allegations and whom they’ll probably discard via free agency soon. Then again, despite what the box score says, the Cubs weren’t winners because of Aroldis Chapman, whose overused arm had no life left. In Game 7, Chapman was the player who made them most likely to lose.

This was the October when relievers evolved, as Terry Francona stretched and prodded his pen into a weapon that could compensate for a short-handed rotation — and, in the process, pressured his peers to adapt. All month, we wondered whether Miller and Chapman would crack under the late-season load; Game 7 gave us our answer. Miller, who’d perplexingly worked with a six-run lead in Game 4, looked mortal, and Chapman, whom Joe Maddon had even more oddly deployed in an all-but-over Game 6, was reduced to slinging sliders and hitting triple digits just once. The postseason started with one manager not using his best reliever; it nearly ended with two more managers using their best relievers too much. If November was the wall, though, the Cubs broke through it, with Maddon bailed out by his Tampa Bay brother Ben Zobrist, whose 10th-inning RBI double was, by championship win probability added, the 16th-biggest hit in World Series history — well behind Rajai Davis’s dinger, which ranks fourth.

On the field, at least, the Cubs won without weak points, asterisks, or reservations. They waited and waited, and when at long last they triumphed, they didn’t do it half-assed. Instead, they pursued the platonic ideal of a championship season. I won’t say whether the 2016 Cubs were worth the wait; that’s a question each Cubs fan has to answer for him or herself, filling in for the many whose vigil lasted so long that they’re no longer around to respond. But from an outsider’s perspective, there couldn’t have been a more convincing close to a drought that wore out its welcome. It’s not often, in baseball, that we get the grounds to say this, so savor it, folks: For once, both the best team and the best story won.

- Apr 9, 2014

- 869

- 339

Last edited:

- Oct 29, 2016

- 23

- 10

couldnt have been happier with this outcome had it have been my own team

SCOTTSDALE, Az. — The Cubs could have made it difficult on right-hander Jason Hammel. They could have picked up his $12 million option, stuck him in their bullpen and depressed his free-agent value next season.

“I really do believe with any other team, I would have been taken advantage of,” Hammel said Monday. “If they would have picked up my option, it very easily could have ended my career.”

Instead, Hammel said, the Cubs honored a commitment they made when they signed him to a two-year, $20 million free-agent contract in Dec. 2014 — a commitment not to exercise his third-year option and trade him.

The history between the two parties helps explain why the Cubs allowed Hammel to become a free agent on Sunday, even though he had a 3.83 ERA in 166 2/3 innings last season. The move seemed curious at the time; teams rarely decline reasonable club options on starting pitchers, knowing how fleeting rotation depth can be.

But the Cubs, according to Hammel and his agent, Alan Nero, remembered the context of their original free-agent negotiations, how Hammel was concerned about the team effectively using the option against him and trading him during that season for the third time in his career.

“It all boils down to Theo’s character, the fact that he lives up to his word,” Nero said of Cubs president of baseball operations Theo Epstein. “Jason is coming off the best season of his life. It’s appropriate for him to be a free agent. Theo took the high road, as he normally does.”

Hammel, now 34, had better offers in Dec. 2014 — offers for three years, offers for more than $10 million annually, both parties said. He took less to return to the Cubs, who had traded him to the Athletics the previous July.

The Cubs did not grant Hammel a no-trade clause for the option year, and one team official said he would not even describe their commitment as a gentlemen’s agreement. But by making Hammel a free agent, Epstein kept his end of the bargain.

Epstein likely could have acquired a fringe prospect or middle reliever for Hammel, but the Cubs will benefit in other ways by simply letting him go; their treatment of Hammel reinforces to players and agents that their front office can be trusted.

“The intent was never to exercise the option and then trade Jason, so we will not consider that path,” Epstein said in a statement. “Instead, Jason will have the opportunity to enter free agency coming off an outstanding season and the ability to choose his next club.”

Hammel and his wife, Elissa, said their strong connection with Epstein and Cubs general manager Jed Hoyer began when the team signed Jason as a free agent in 2014, and actually grew stronger when he was traded to the A’s.

Elissa was pregnant at the time, as were the wives of both Epstein and Hoyer.

“Elissa was in the lobby with me as we got traded,” Hammel said (the Cubs were in Washington at the time.) “She ran into Jed. She was bawling her eyes out.

“We were like, ‘We pitched so well, there’s no way you’d actually trade us.’ It kind of resonated with them, how that move was so crazy for us. I think they understood what was going on with our family.”

Said Elissa, “We established a good relationship with them personally and professionally where there was mutual respect for not just using us as a chess piece, but really kind of caring about their players and their players’ families, which is really why they succeeded this year.

“The families of the Cubs’ organization are treated like gold. And they know how that affects the player. I don’t think it’s just us. They know there is a ripple effect. You keep the family happy, you keep the player happy and the players can perform. They followed that mantra the entire time we were there.”

arstyle27

Supporter

- Nov 13, 2001

- 10,630

- 3,614

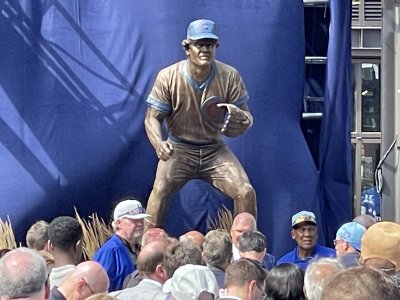

Finally made it down to Wrigley before the heavy construction starts tomorrow. It was beautiful.

View media item 2224524

View media item 2224525

View media item 2224526

View media item 2224524

View media item 2224525

View media item 2224526

- Sep 7, 2011

- 1,915

- 531

Rizzo and Heyward both win Gold Gloves.

Russell came up short. he will win a Gold Glove next year i'm sure.

- Nov 18, 2007

- 28,138

- 9,299

Rizzo and Heyward both win Gold Gloves.

Russell came up short. he will win a Gold Glove next year i'm sure.

You are a Cubs fan and I am a Giants fan....so I am hoping we can try to be fair here....

But what exactly is it that leads you to believe that Russell will all of a sudden be the best defensive shortstop in the National League next year? Is it just because he is young and you expect him to get better? Because statistically, he ranks lower than Crawford in every single statistical measure. In fact, Freddy Galvis ranks ahead of Russell and Seager isnt much behind him.

Just curious. You clearly watch more Cubs games than I do. But statistically speaking, he is a ways away from being "sure he will win next year."

Lake Shore Drive

formerly slp product

- Feb 8, 2005

- 7,336

- 2,445

Still waiting for my world series champions fitted.

Anyone in the CHI copped one yet?

Last edited:

I didn't get the Champion, but I got a black Cubs fitted, 2 World Series, and a regular with Bryant and Rizzo sigs sewn on, plus a Bryant shirt and World Series Champs shirt.

I been spending in Oregon.

I'm def gettin the Blu Ray set I've seen online. Can't wait for that.

I been spending in Oregon.

I'm def gettin the Blu Ray set I've seen online. Can't wait for that.

DeadsetAce

Supporter

- May 31, 2004

- 107,855

- 54,049

I didn't get the Champion, but I got a black Cubs fitted, 2 World Series, and a regular with Bryant and Rizzo sigs sewn on, plus a Bryant shirt and World Series Champs shirt.

I been spending in Oregon.

I'm def gettin the Blu Ray set I've seen online. Can't wait for that.

RIP to CP's daughter's college fund

i don't blame you

Serious, I'm gonna spend, I have no choice.

I was in day 1 of Theo's hiring. We got laughed at and mocked in the Central thread and the MLB thread.

I made this one so I could track the team in peace, every pick, trade, signing, scouting report, rumor, etc.

I'm gonna enjoy this winter no matter the cost. Hell, I miss watching them play already.

I was in day 1 of Theo's hiring. We got laughed at and mocked in the Central thread and the MLB thread.

I made this one so I could track the team in peace, every pick, trade, signing, scouting report, rumor, etc.

I'm gonna enjoy this winter no matter the cost. Hell, I miss watching them play already.

- Jul 10, 2005

- 1,288

- 65

^ Im still waiting for all my WS gear from last week . DSG and MLB are slow at processing my order. Oh and just got the locker room knit that i've been wanting since i saw it during the parade. cant wait for those.

yes they will be rocked all winter long....been waiting enough....

yes they will be rocked all winter long....been waiting enough....

Lake Shore Drive

formerly slp product

- Feb 8, 2005

- 7,336

- 2,445

Finally got my shipping confirmation from MLB.com

Lake Shore Drive

formerly slp product

- Feb 8, 2005

- 7,336

- 2,445

- Apr 9, 2014

- 869

- 339

That's the hat I want. The traditional one with that on the side. I don't care for the flashy ones that says Championship across it. I have like $300 of stuff I want to pull the trigger on, but every time I go to check out, I'm adding/removing stuff and can't make up my mind

- Sep 1, 2007

- 8,131

- 618

still waiting on my tihs