The Year in Movies

How Hollywood bounced back from a miserable 2011. Plus: The top 10 of the year!

By Zach Baron on December 20, 2012PRINTSo it wasn't the greatest year for movies in the history of mankind. Maybe it wasn't even the greatest year for movies in the history of this short, savage decade — 2010 had Black Swan and Winter's Bone and The Social Network, The Fighter and Inception and True Grit, Blue Valentine and The Town and Toy Story 3. The highest compliment we can really pay 2012, if we're being honest, is probably something along the lines of: It wasn't 2011.

Still, it was pretty great. Michael Bay did not make a movie. Paul Thomas Anderson did. Our 2012 Best Picture winner will have sound and color and a judicious, restrained attitude toward whimsy and tap dancing. (Well — maybe strike that about the tap dancing.) Steven Spielberg made a movie about a man instead of a horse. This summer's comic book movies were better than last summer's comic book movies. There was no seismic shift, exactly — not in a year when there was something called Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter — but a wobbly industry seemed to find its balance. Yes, there were wildly cynical brand extensions (Battleship), unasked-for sequels (MIB3),

a movie in which Ryan Reynolds failed to guard an empty building (Safe House). But going to the movies this year was mostly a buoyant, cheering experience. There was a sense that something went right.

I guess I'm trying to figure out what that something was.

It was a reasonably good year for women on-screen — Jennifer Lawrence, Jessica Chastain, Quvenzhané Wallis, Amy Adams, Kara Hayward, Kristen Stewart, Marion Cotillard, Helen Hunt, Keira Knightley, Emma Stone — and off, as Kathryn Bigelow made the astonishing Zero Dark Thirty, a movie financed and distributed by wunderkind producer Megan Ellison's Annapurna Pictures. (Ellison is also responsible for The Master, Lawless, Killing Them Softly, and next year's Spring Breakers, and I will totally go halves on the Vermont Teddy Bear if you want in.) They say in Hollywood that it takes two years for studios to react — we won't get the inevitable slew of comedies contending for 2011's Bridesmaids money until next year. But there was something to the New York Times Magazine's decision to do a "Hollywood Heroines" cover a couple weeks back. The performances that lingered in 2012 were those by women, even in male-dominated movies, whether by Wallis, who may not have even been acting, but who incarnated a kind of kinetic wonder in Beasts of the Southern Wild, or Lawrence, a dutiful franchise anchor in The Hunger Games and a vengeful force of screwball nature in Silver Linings Playbook.

But that's not it, exactly.

Nor is it the string of auteur directors who went back to work this year — Anderson and Bigelow and Spielberg, David O. Russell and Ang Lee and Robert Zemeckis, Ben Affleck and Quentin Tarantino and Steven Soderbergh, Wes Anderson and Whit Stillman and Oliver Stone — not just in the prestige-oriented fall but in the spring and blockbuster summer, too. Somehow, they let Joss Whedon direct The Avengers. Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight Rises marked the end of what is so far the most influential trilogy in this century — even Bond movies are Batman movies these days. Ridley Scott made a proudly perverse blockbuster in Prometheus, a storm of alien C-sections, robot Michael Fassbender, and vague, Lost-like questions about the soupy origins of mankind. It was visually astounding, impenetrably convoluted, and made $402,486,687 worldwide.

But that's not it either.

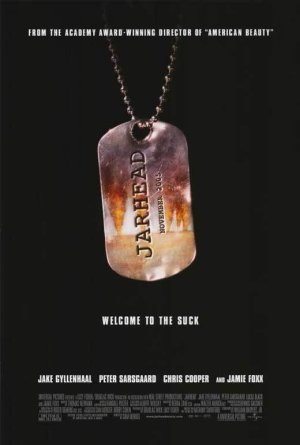

Hollywood has been trying to grow a new crop of stars for what feels like an uncomfortably long and fruitless amount of time (cf Tobey Maguire, Jake Gyllenhaal, Ryan Reynolds, and the newest addition to their biweekly support group, Taylor Kitsch). But in 2012 we finally ended with a handful of actors and actresses who seem legitimately destined to be with us for a while. So welcome the aforementioned Lawrence, Stewart (who went from moping teen and/or lascivious sex-child to genuine action star in not one but two movies this year, the Twilight finale and Snow White and the Huntsman), Stone, and the magical charisma unicorn that is Channing Tatum. Tatum starred in three modestly budgeted movies in 2012 — 21 Jump Street, in which he turned out to be funnier than Jonah Hill; The Vow, a romantic trifle made solid and charming by Tatum's single-minded commitment to be the greatest boyfriend an amnesiac Rachel McAdams ever had; and Magic Mike, in which the actor rode Ginuwine's "Pony" to stripper immortality — all of which were among the year's top 25 highest-grossing films. Put him in anything. He can't talk, but it'll be great.

So perhaps that's it?

Or you could just look at your nearest theater marquee — it's Oscar season now, and there are few (if any) bad choices. The eventual Best Picture winner will be Lincoln or Zero Dark Thirty, probably. (My bet: Lincoln.) But right behind those two films are Silver Linings Playbook, the wildly enjoyable Django Unchained, Argo, and some assortment of Life of Pi, Beasts of the Southern Wild, The Master, Amour, Rust and Bone, Moonrise Kingdom, and Anna Karenina. You will have noticed I have not mentioned Les Misérables, but then perhaps you also noticed the time I threatened to burn down the Academy if it won. I am not proud of that statement, exactly. I would like to apologize, actually. Nominate it, by all means. But I will burn down the Academy if it wins.

There was no lacking moment for movies this year — not in January, when the taut, brutal thrillers The Grey and Haywire came out; not in February, when Josh Trank announced himself as a future franchise auteur with the sci-fi found-footage curio Chronicle; and not in March, which in addition to The Hunger Games gave us the year's best action film in The Raid: Redemption. Not this summer, when Whedon pulled off The Avengers, Beasts of the Southern Wild saw ever-wider release, and even a rushed Spider-Man reboot showed signs of life — or at least signs of Emma Stone and Andrew Garfield. 2012's August doldrums were enlivened by David Cronenberg's Cosmopolis and John Hillcoat's Lawless. The Master bowed two weeks later and it's been one great film after another ever since.

This is a long-winded way of saying we did OK this year. But I still haven't accounted for that buoyancy — that sense that after a deeply dispiriting 2011, the pendulum swung back our way.

Weinstein Co.

I have this running joke with my mother that she doesn't like movies unless she likes the characters in them. "Hated the Master," she texted me this fall. "No family values!" That second part is her being deliberately provocative, though it's also true — she likes movies in which she can recognize herself, or at the very least relate to the people on-screen. I make fun of her for this — she is an otherwise extremely smart and sophisticated woman who just happens to like happy endings and characters who are good at heart. Not for her, Joaquin Phoenix's staggering, loathsome drunk. Never mind he's supposed to be that way: fearsome, dangerous, corroded from inside out. She can't stand the two hours she's supposed to spend in his presence.

Zach Baron's 10 Best Movies of 2012

1. Zero Dark Thirty

Because Kathryn Bigelow makes films like they're bombs about to detonate in her lap. Haunting, unflinching, never less than absorbing, with aspirations toward not just art but the "truth," even as the film never stops questioning the very notion of such a thing.

2. Silver Linings Playbook

It's romantic, yeah, and about my hometown sports team, which is half the story. The other half is Jennifer Lawrence's serrated performance and that fleeting, cheering possibility of redemption, even if none of us has quite earned it yet.

3. The Master

I am a bear, and Jeff Wells, and that white-on-blue ship's wake I can still see, even now.

4. Django Unchained

Quentin Tarantino's slavexploitation flick is slacker than Inglourious Basterds and much harder to watch in a room full of cackling white people, but it's also legitimately funny, not to mention righteously, thrillingly angry, too. That moment Jamie Foxx rides a Rick Ross song onto Leonardo DiCaprio's plantation? I would inject that moment into my arm if I could.

5. Beasts of the Southern Wild

The year's least self-conscious film was probably a little wide-eyed in its magic-filled take on a splinter Lousiana community trying to survive a suspiciously biblical flood, but don't tell that to Quvenzhané Wallis, a tiny force of nature with the kind of presence and poise that can knock down walls. The most surprising and heartening thing I saw on a screen this year.

6. Argo

A '70s throwback thriller that was also the best Hollywood self-satire in years. So what if he wrote in a seductive shower scene for himself? CIA agents making fake science fiction movies under dubious Canadian cover need to take showers too, don't they?

7. Magic Mike

In which, for the first time in a while, Steven Soderbergh finds something worthy of his singular eye: Channing Tatum, doing backflips to "Pony."

8. Moonrise Kingdom

Wes Anderson, long our foremost chronicler of childlike adults and adultlike children, finally makes a movie about how they all got to be that way. No one sees better how strange, how erotically charged, how downright confusing and full of possibility the world is to those who are small and haven't had it beaten out of them yet. Hopefully these two never will.

9. Damsels in Distress

A total disaster, but what a disaster — odd but sincere, full of tap-dancing and coded laments about conniving men whose religious beliefs obligate unholy sexual practices. Whit Stillman is the kind of guy who thinks there's something romantic in a frat boy who would remember what color your eyes were if only he weren't dumb and color-blind. Come to think of it, so do I.

10. Lincoln

Like certain legends it depicts, this one grew in the telling for me — I started off bored, and came away amazed. A movie about things you can't put on film. And yet somehow they're there.

Anyway, it's always struck

me as wrong, this notion that we're supposed to look at the screen and see things that reaffirm who we already are, what we already like. Movies, I try to tell her, probably obnoxiously, should do just the opposite — discomfort us, tell us things we didn't already know, make us second-guess the things we thought we did. But lately I've been wondering if there's less distance between us than I'd like to admit. There's something to — if not seeing yourself onscreen — feeling like a movie has something to say about our lives. That's kind of why we go, right?

Not to dig up the ghost of 2011 once more, but that's ultimately why last year at the movies was so galling. Not because the overall quality of the films was poor, though it was. But because movies last year felt so solidly disconnected from life as we were living it. Whether the green-screen revisionism of Transformers: Dark of the Moon — JFK put a man on the moon because: robots — or the empty, ineffectual escapism of Cowboys & Aliens or the Oscar-season retreat into timeless nostalgia (The Artist, Hugo, Midnight in Paris, etc.), movies in 2011 seemed not just blind but openly hostile to whatever moment it was that we found ourselves in. Not for nothing was last year's Academy Awards ceremony a blinkered journey into cinema's silvery past. Watching it you would've had no idea whether you were in 2012 or 1998, 2004 or 1991.

That's the thing the movies got right this year. That feeling that you could look at a screen and recognize some glimmer of life as we live it now. Sometimes this was obvious, straightforward: Bigelow's starkly realistic Zero Dark Thirty begins with a panicked scrum of 9/11 calls and coolly proceeds through the next 10 years of black sites and torture chambers and far-flung conference rooms full of bleary-eyed bureaucrat-assassins, portraying the hunt for Osama bin Laden not as a march toward long-overdue justice but as a maze from which we still may not have fully emerged. Carefully reported, slyly shot, and deftly acted, Zero Dark Thirty is as grim as it is exhilarating. Bigelow holds up not an argument but a mirror.

So does Spielberg's Lincoln, another movie to peel back a treasured American narrative and show the compromised process and ordinary, flawed men behind it. Lincoln is about not just the present day, in its pointed allegory of moving liberal legislation through a divided and corrupt political system, but the fundamental messiness of any grand project — the way that doing the right thing is always contingent and rarely inevitable. Andrew Dominik's Killing Them Softly was even more blunt about the parallels between criminal codes and those who rule in American business and government. Benh Zeitlin's Beasts of the Southern Wild was a dizzyingly impressionistic movie about the desperate magical thinking of splintering communities foundering in neglect. And on it went — Anderson's The Master, about the postwar moment when a certain kind American faith and sense of purpose was eclipsed by cynical opportunism; Affleck's Argo, an espionage thriller that was also a barbed espionage farce; Tarantino's Django Unchained, which shows in discomfiting detail the ugliness of the historical period it proceeds to gleefully rewrite. Even Nolan's Dark Knight Rises took as its setting a Gotham stricken by class divisions, ruled by a government that had abdicated its responsibilities.

All of these films were about, in thoughtful and sometimes surprising ways, the present moment. Who are we, how did we become that way? Movies in 2012 had answers for these questions — and not always political or historical answers, either. Silver Linings Playbook, in addition to being the year's best romantic comedy, was also 2012's best sports movie, because it considered so deeply how a game like football might affect our daily lives — how the fortunes of a team might come to reflect our own, how a city reckons with its identity through the proxy of the games played in its stadiums. There was the mumbly Florida working-class anomie of Magic Mike, the brutal and unsubtle reality-TV satire that was Hunger Games, the lament for a bygone communal spirit and common project in Promised Land. There was even Project X, the colossally exploitative found-footage party flick that was nevertheless an exceedingly accurate depiction of How We Flipcam and Teen-Talk Now.

Meanwhile, many of the year's more cynically positioned projects — the empty bombast of John Carter; the winking, self-loathing soap-opera kitsch of Dark Shadows; the pointless, lackluster reboots and unwanted sequels — were largely punished by audiences who seemed to recognize when they were being condescended to. It felt — rightly or not — like a year in which viewers set their own agenda, in which moviegoers rewarded quality and engagement over smarmy taglines and knee-jerk nostalgia. (Then again, the five highest-grossing films this year, in order: The Avengers, The Dark Knight Rises, The Hunger Games, The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn — Part 2, and Skyfall. We are not done with franchise films. But perhaps we are done, at least for a bit, with the ones made without a hint of care or ambition.)

Hollywood is a business. An entertainment business, specifically. It has no obligation to teach us anything. People go to the movies to escape as much as they go to learn, or to be challenged, or to be made uncomfortable. The industry has no higher purpose, nor should it: Its job is to make things audiences want to see. And in 2012, it emphatically succeeded at that task. Box office is up this year so far, and we seemed poised for a genuinely suspenseful Oscar race, "if the scattered and contradictory results of the last couple of weeks — which have seen the Golden Globes and various regional critics associations split their votes widely among Zero Dark Thirty, Amour, Lincoln, Moonrise Kingdom, Les Misérables, Silver Linings Playbook, and a host of other films — are any indication."

As in past years, that Oscar race will be less about some abstract notion of quality and more about the Academy's vision of itself. Is Hollywood a place that should be making serious, unflashy, sternly educational films for adults like Lincoln? Is its role to shock, as with Zero Dark Thirty? Or to entertain, as with Les Misérables? Should movies strive to reaffirm our basic humanity and sense of possibility, as with Silver Linings Playbook? Or should they trouble us, challenge us, even confuse us, as with The Master? None of these aims, of course, are mutually exclusive. One of the wonders of 2012 is that the movies managed to encompass them all. And there is a comfort, even a kind of happiness, in knowing that no matter what wins, we will be able to look up at the screen and see ourselves looking back.

@ the RR dig.

@ the RR dig.