- Jan 16, 2011

- 15,009

- 36,451

Still trying to understand how Bolivia got their flag colors and they are in South America

Speaking of them...

Afro-Bolivian monarchy - Wikipedia

Lithuania also uses the same colors.

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

Still trying to understand how Bolivia got their flag colors and they are in South America

Unrelated but your screen name sounds like a Bobby Shmurda burnerStill trying to understand how Bolivia got their flag colors and they are in South America

www.instagram.com

www.instagram.com

Don Carlos is not the only self-styled cowboy riding on Ouagadougou’s streets – horses are a big part of Burkina Faso’s cultural identity. This relationship dates back to the country’s origin story in the Middle Ages. According to oral tradition, the legendary African princess Yennenga was once a horse-riding warrior so revered that her father refused to let her get married. One day, the princess escaped her father’s custody and had a son with an elephant hunter of a neighbouring tribe.

Nicknamed “the Stallion”, Yennenga’s son went on to found the Mossi kingdoms, a number of independent kingdoms established on Burkina Faso’s territory, until the French colonised the area in 1896. The kingdoms were once very powerful in West Africa, and horses were a vital part of their military and culture, signalling status and wealth.

https://www.vice.com/en/article/epdn9z/burkina-faso-presidential-election

Today, the Mossi are still the largest ethnic group in the small West African country. Although colonialism brought an end to the kingdoms, a descendant of the throne exists to this day. Naba Baongo II is the current Mogho Naba, or King of the Mossi. His role is mainly ceremonial – for instance, he heads a procession of hundreds of horses in the capital every Friday, symbolising his ministers dissuading him from going to war. The exact origin of the war has been lost over the centuries.

Horses are still beloved in Burkina Faso, and feature on the country’s coat of arms and in celebrations like weddings. Horse racing is one of the country’s most popular sports – every Sunday, the capital city stops to watch the races at 3PM. Ali Faso, a celebrity stable owner, takes care of the horses of wealthy people in the area, and often takes young people under his wing. "With a little luck, some become coaches,” Gillier said. Many other horse enthusiasts end up looking after cattle, on horseback, on the pastures surrounding the Tanghin 2 Dam in the northern part of the city.

Anatomy of A Song: “Zangalewa” From African Protest into Multiplatinum Pop

Think “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin-to-Die Rag” by Country Joe McDonald in 1967--a broad satire unleashed at America’s Vietnam War. Transpose that to Cameroon, and a satire aimed at the Eurocentric legacy in independent Africa: “Zangalewa.” Performed by Cameroon’s Golden Sounds in 1986, the song became an anthem across Africa, crossed the pond to Latin America, and ended up with its core message inverted in Shakira’s multiplatinum hit “Waka Waka: This Time for Africa.”

The Golden Sounds (Jean Paul Zé Bella, Dooh Belley, Luc Eyebe and Emile Kojidie), oddly enough, were active members in Cameroon’s presidential guard. The song’s lasting success stems largely from its very infectious military-march rhythms. The lyrics, due to the multilingual nature (up to 600 languages) of Cameroon, skip around between French, Douala, Pidgin English, Fang and perhaps Ewondo. Of course, there are “left, right, left right” marches, but then the song is really about the grievances of the ordinary recruit: lousy pay, bad food, punishing training, etc. And they also really lay into the brass: their fat and abusive drill instructors who scarf down a yummy assortment of sugary beignets while threatening to shave recruits’ heads and send them to prison.

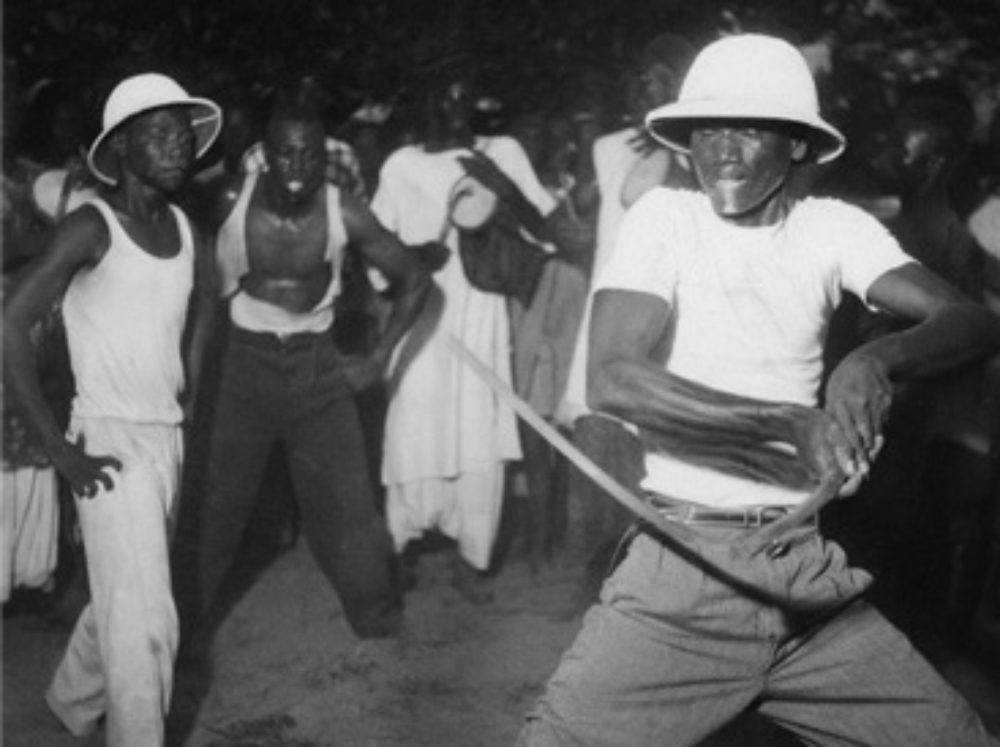

Music video caught on quickly in Africa in the ‘80s. The full meaning of “Zangalewa” was actually realized in the remarkable video, which superimposes the band lip-syncing the song over Cameroonian military parades, apparently using bluescreen. The band members are wearing uniforms stuffed with pillows to create comedically large bellies and behinds, with “big belly” repeated in the lyrics. At one point a band member whirls around and appears to be hectoring a vast formation of soldiers assembled down below him.

The satiric look takes three very significant steps further: the band members are wearing pith helmets, brandishing bâtons swagger, or swagger sticks, and are in half whiteface. Bâtons are totally obsolete. They come from ancient times, Napoleon thought they were essential, and they resurfaced as hot items for Generalfeldmarchallen in the Third Reich. Swagger sticks, too. They were largely abandoned after World War I, and only egomaniacs like Patton used them after that.

The pith helmet you see on “Zangalewa”’s record label was headgear the colonial powers issued to their soldiers in the “hot tropics.” Neither swagger sticks nor pith helmets have anything to do with Cameroon’s military. So, along with the whiteface, “Zangalewa” becomes a protest against Cameroon holding onto too many pernicious colonial practices. Swagger sticks, pith helmets, and especially whiteface, strongly signal collaboration. After a nation is subjugated by a foreign power, that’s really the worst crime you can commit. For example, Iraq.

This is nothing new. French New Wave documentarian Jean Rouch’s most controversial film Les Maitres Fous showed us how African culture included ritualized satire of colonial masters. What did the Nigeriens pantomiming their oppressors in Rouch’s film wear on their heads? Pith helmets.

The infectious beats of “Zangalewa” were covered across Africa, from South Africa, to Nigeria, to Cote’d’Ivoire, to Ghana, to Senegal (Momar Gaye and Zaman’s being the best. Marchable, and also very danceable. Across the Atlantic, it would be heard in Suriname, the Dominican Republic, and especially Colombia.

Blacks in Cartagena, Colombia responded enthusiastically to African styles including soukous and highlife in the 1980s, developing their own champeta style. “Zangalewa” was a natural there, recorded by Los Condes. But Latin American covers of “Zangalewa” were retitled “El Negro No Puede,” with lyrics about a Black man who cannot sleep, presumably impeded by nonstop partying. No soldiers in videos for these covers, either – just women writhing in lingerie, ubiquitous in early MTV days.

Trevor Noah, host of The Daily Show, really irritated the French two years ago when he said “Africa won the World Cup,” because Les Bleues were predominantly of African heritage. That being said, no African country has ever won the World Cup, and the entire continent really craves this prize. When Senegal’s Teranga Lions team beat France in 2002, all of French West Africa went bonkers.

No smaller controversy erupted earlier when FIFA announced superstar Shakira, backed by the South African multiracial fusion band Freshlyground, would perform the latest cover of “Zangalewa,” entitled “Waka Waka (This Time for Africa).” The song is beloved across Africa, so why isn’t an African artist performing it? Shakira is half Lebanese, her name means “grateful” in Arabic, and she uses Arabic scales--but that was not close enough. Like the “telephone game” in which children in a circle whisper something into the ear of the child sitting next to them, the original historical perspective and satiric thrust of “Zangalewa”’s lyrics and video were long gone in a blur of lingerie by the time Shakira got to the song. Her lyrics do not question authority in the military. Quite the opposite. From “You're a good soldier” to “You're on the front line,” they nakedly equate soccer performance with an unquestioned and unquestionable military duty.

Despite mixed reviews, “Waka Waka (This Time for Africa)” inevitably went multiplatinum, the second success for the diva since her “Hips Don’t Lie,” and its video, with Shakira in skimpy, fringy, “African” dancewear, also topped the charts. Surviving members of Golden Sounds in Cameroon did not receive a penny from this, but they did not sue Shakira for plagiarism; one bandmember had admitted the chorus came from Cameroonian “sharpshooters who had created a slang for better communication between them during the Second World War.” A rumor circulated that the lyricist behind “El Negro No Puede” was suing Shakira, but he later denied it.

dj.henri is a New York City DJ who has performed at the Apollo Theater, B.B. King’s, Symphony Space, and elsewhere. He is also the creator of radioafricaonline.com.

An African immigrant's pizza wins global raves — and overcomes Italian prejudices

January 30, 20228:52 AM ET

Ian Brennan

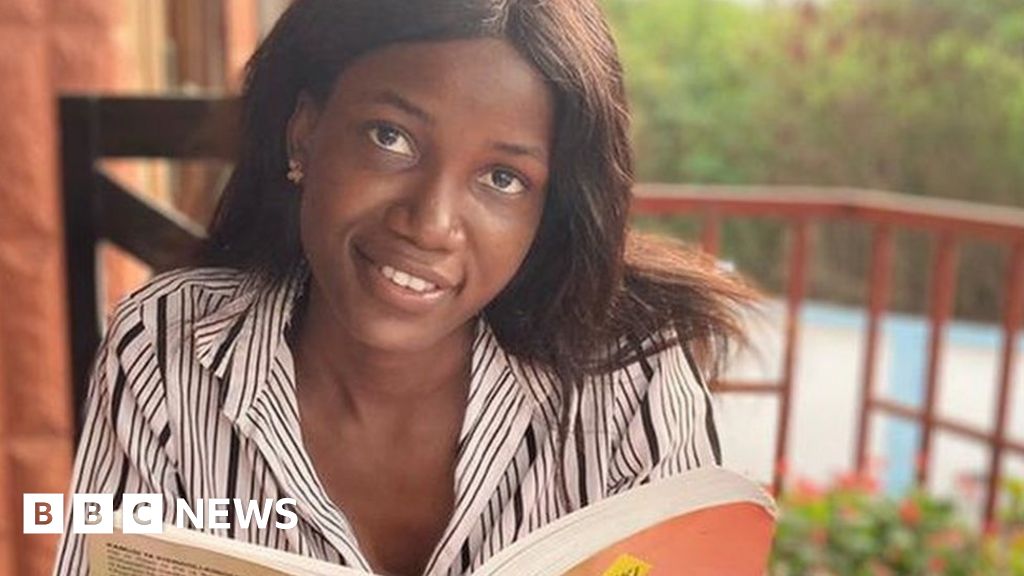

Ibrahim Songne, an immigrant from Burkina Faso, opened a pizza spot called IBRIS in the Italian town of Trento. He overcame local prejudices — and now has been named to a list of the world's top 50 pizzerias.

Marilena Umuhoza Delli for NPR

After immigrating to Italy from Burkina Faso at age 12, Ibrahim Songne tasted pizza for the first time. His reaction?

Disgust.

"I'd never even heard of pizza before I arrived in Italy. I took a bite and found it gross and completely tasteless."

Despite that inauspicious start, Songne went on to take out a loan to open a pizza joint — and in late 2021 the 30-year-old's pizzeria was named one of the top 50 in the world. 50TopPizza.it calls Ibrahim's dough "perfectly leavened" and the recipes "imaginative."

Ibrahim christened his restaurant, IBRIS— an all-caps hybrid of his first and last name. Before he opened the small shop in downtown Trento 3 years ago, he says that locals warned him, "A Black man behind the counter will drive every customer away."

These fears seemed realized when on the first day open, Ibrahim stood behind the counter and a middle-aged couple entered. Silently, the pair surveyed the pizza on display, he remembers. Then, he says, they likely assumed that someone of African descent didn't speak Italian, remarked, "This pizza looks amazing. Too bad they let Black people work here" and left.

Article continues after sponsor message

In 2022, it's a very different scene. With only three small benches for seating, lunchtime patrons pack IBRIS' narrow storefront, shouting orders over the Afrobeats soundtrack.

A recipe for success

Ibrahim's success is hardly due to lack of competition. Two other pizza places sit on the same block and another seven are within minutes' walk.

He says his pizza distinguishes itself due to the "intensity, texture and sense of experimentation."

Over the past decade, "crunch pizza" became a trend in northeastern Italy — Crunch pizza customarily has a lightweight but multi-layered dough— that is sometimes fried— and makes a loud crunching noise when bitten into. Ibrahim has created a subtler version of this crispiness.

As for the experimental toppings, they reflect Songne's belief in Italy's zero kilometer food movement, using locally and seasonally available fresh ingredients whenever possible. Working side-by-side with his younger brother, Issouf, he changes the pizza menu daily and includes non-traditional ingredients like purple-potato cream, saffron and ceci bean (chickpea).

Ibrahim Songne is a big believer in local — and sometimes unconventional — pizza toppings. His narrow storefront is packed with pizza lovers.

Marilena Umuhoza Delli for NPR

A rough start to a new Italian life

Today, Ibrahim lives within Trento's picturesque cobblestoned center. One of the nation's wealthiest cities, it is frequently ranked high for quality of life.

It's a great contrast to his younger years. Growing up over a 4-hour drive from Burkina Faso's capital of Ouagadougou, Ibrahim and his parents lived without electricity or running water. In search of work, Ibrahim's father immigrated to Italy; the family later followed.

Upon arriving in Italy's mountainous north in 2004, Ibrahim says he was the only Black student in school and became further isolated due to stuttering.

His desire to undergo speech therapy spurred him to take on part-time jobs as a teenager, a path that led to working in a pastry shop. It was there that he developed a passion for baking.

In the years following, Ibrahim taught himself how to make pizza. Having worked at the pastry shop, he'd tired of sweets and decided to pursue salty flavors. His roommate served as "guinea pig" and Ibrahim grew "obsessed" with developing the consummate pizza dough recipe. He knew he'd found it when he landed on a formula featuring lievito madre — "mother dough, " a natural yeast where the same sourdough starter is used perpetually. Ibrahim has used the same mother yeast for over five years now.

Today, Ibrahim defines himself as 100% Italian and Burkinabe, "but most of all, I am resilient."

"Once I'd overcome my stuttering, I was free. After that, I knew I could face anything."

Helping others with 'suspended pizza'

He's not forgotten his roots. En route to the airport on the day Ibrahim left Burkina Faso for Italy, he entered the city for the first time and witnessed a small boy standing naked, begging on the streets. A passing Burkinabe businessman tossed a candy onto the ground "as if the boy were a dog" and the child scurried after the candy. At that moment, Ibrahim says he decided he would devote himself someday to helping others who are hungry.

After witnessing so many people struggling to make ends meet during the COVID lockdown, pizza and Songne's charitable urges merged. Inspired by the Neapolitan tradition of caffè sospeso ("suspended coffee") — where cafe clientele pay for an additional coffee that bartenders later give anonymously to those in need — Ibrahim expanded the custom to pizza. Soon, pizza sospesa spread to restaurants throughout Italy.

Ibrahim's positive personality and fluent Italian (with what locals describe as a "perfect" Trentino accent) has endeared him to customers.

Marilena Umuhoza Delli for NPR

Rising up despite racism and anti-immigrant feelings

Ibrahim's success is all the more notable given the history of Italy – and his home province.

Racism is part of the country's past and present.

During the renaissance, young African children referred to as mori ("the dark ones") were used as household slaves in wealthy Venice households. In recent years, Italians have hurled bananas at Italy's first Black governmental minister, Cécile Kyenge, and Italian-born and -raised soccer star, Mario Balotelli. In 2021, the national television network, RAI, refused to officially ban Blackface following an uproar over Blackface impersonations of Beyonce and other musicians.

Anti-immigrant sentiments also run strong.

Filomeno Lopes, one of the first and most prolific Italian African authors and a host on Radio Vaticana Italia (Vatican Radio), states, "Ibrahim dared to get out of the kitchen — where behind closed doors immigrants clean dishes and furtively prepare the meals — and instead to lead in a field that Italians consider their own. By doing so, he's forged a new path to citizenship."

Trentino presents its own challenges.

The current president of the Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol region is a member of the far-right, anti-immigration Lega Nord political party. The IBRIS storefront signs have been vandalized, and photos have appeared on social media of teenagers standing outside the restaurant and making obscene gestures.

Nonetheless, Ibrahim's contagiously positive personality and his speaking fluent Italian with what locals describe as a "perfect" Trentino accent has helped endear him. He has even mastered Trento's regional dialect – and of course – as his new pizza honors prove – he's a maestro of the Italian pie.

"Once they taste my pizza, all judgment disappears," says Ibrahim Songne.

Marilena Umuhoza Delli for NPR

A pizza fan club

On a recent Thursday afternoon, 52-year-old Alessandra Gelva sat huddled excitedly on one of the pizzeria's benches with her two teenage children and a friend.

"This pizza is beautiful. It is the only place we ever come for pizza. The toppings are so original. The pistachio is one of my favorites."

Another regular, Giuliana Passamani, 60, describes IBRIS' pizza crust as "superlative."

35-year-old Maria, who declined to give a reporter her last name, gushed that she "comes here three times a week from over an hour away. He is famous."

"Big things start little," says Ibrahim. "If given enough care and value, food can change the world. It's a bridge between people — a way to pleasurably experience something new. That experience then can lead to greater tolerance and understanding.

"Once they taste my pizza, all judgment disappears."

Ian Brennan is a Grammy-winning music producer (Zomba Prison Project, Tinariwen, The Good Ones) who has recorded 37 records by international artists across four continents. He is the author of seven books. His latest, Muse-$ick: a music manifesto in fifty-nine notes, was published last fall by Oakland's PM Press. He has lived in Italy since 2009.

Photos, translation and additional reporting by Marilena Umuhoza Delli, an Italian Rwandan photographer, author and filmmaker. She has written two Italian-language books about racism and growing-up with an immigrant mother in Italy.

Looks like October 18th is the publish date

Nah I went to a predominantly white high school. Some of my reunion photos would look like this excluding my family.

The craziest photo ever