The Cubs just replaced Aroldis Chapman, acquiring Royals closer Wade Davis for outfielder Jorge Soler.

Wait, that’s it? Seriously? In July, the Cubs sent four players — including their top prospect, Gleyber Torres — to the Yankees for two months and a playoff run of Chapman, and now they’re getting Davis for Soler alone? Royals GM Dayton Moore is going to reach into his pantry tomorrow morning, shake the coffee can labeled “promising former Cubs” and discover, to his utter shock, that Soler’s the only thing that falls out.

In this day and age of Billy Beane and Theo Epstein clones running teams, there are risky deals, or trades where one side wins but the other side wins more. But it’s not often that you can’t at least make an argument for both sides of a transaction.

This is one of those rare cases. This is a steal for the Cubs.

But in the interest of understanding different viewpoints, and not just saying, “Wade Davis is good and Jorge Soler isn’t, really,” let’s build a case for Soler being equal value for Davis.

The Royals are in a transitional phase; after following up back-to-back pennants with an 81-win season, they head into 2017 with Davis, Lorenzo Cain, Eric Hosmer, Danny Duffy, Mike Moustakas, Alcides Escobar, and Jarrod Dyson ticketed for free agency after the season. That’s a lot to replace for anyone, much less a small-market team like Kansas City. So this is a ****-or-get-off-the-pot moment for Moore, in which he can cash in on the roster that won the World Series in 2015 and try to build the next good Royals team, or he can roll it all back out there and give it one more shot.

Whatever happens to the rest of that group, Davis was a prime candidate to be traded. “Relief pitcher performance is volatile” has taken on catechetical importance as an axiom for baseball folks, and it applies here: Davis is 31, set to make $10 million in 2017, and he went on the DL twice last year with a forearm strain, which is one of those scary phrases that often presages Tommy John surgery.

Since he moved to the bullpen full time in 2014, Davis has mostly run out a three-pitch mix: fastball, cutter, curveball. In 2014 and 2015, when he was his most dominant (420 ERA+ over those two years), his velocity would be down early in the year, but once he got going he’d average between 96 and 97 mph on his four-seamer and about 93 on his cutter, using Brooks Baseball’s month-by-month data.

In 2016, Davis’s hard stuff was down about a mile per hour across the board. That doesn’t mean he’s about to blow out, but it’s a data point.

Soler, meanwhile, is a mountainous 24-year-old slugger who’s under team control through 2020. He was part of the Yoenis Céspedes–Yasiel Puig wave of Cuban sluggers, and the Cubs inked him to a $30 million contract in mid-2012, when he was only 20 years old. Soler, listed at 6-foot-4 and 215 pounds, has the kind of muscles you get from eating five dozen eggs every morning, which means he can do this:

Perhaps as a tribute to Kansas City’s Power & Light District, the Royals have traditionally been light on power. Kendrys Morales just posted the Royals’ first 30-homer season since 2000, and only the 11th in the team’s 48-year history. No Royal has ever hit more than 36 home runs in a season. Soler has the swing and the pedigree to anchor a lineup, for potentially as little as $17.7 million over the next four seasons. For a free-agent-closer-to-be who’s at risk of blowing out, that looks like quite a haul.

Unfortunately, that reading of the situation leaves out a few key details.

First, while Davis is at risk of his arm coming off just like any other pitcher, he hasn’t had Tommy John yet, nor is it certain that he’ll need to. The reason “forearm strain” is so scary is that what feels like a strain to the flexor-pronator mass, the group of muscles and tendons that allow a pitcher to grip and throw a baseball, is actually damage to the ulnar collateral ligament — the ligament that gets replaced in Tommy John surgery — which sits behind the flexor-pronator mass.

The injury Davis suffered wasn’t a flexor-pronator strain — he pulled a muscle in a different part of his forearm, the Royals said at the time. He might still be at increased risk of tearing his UCL, but he doesn’t have one foot in the operating room.

Moreover, Davis came back after he got hurt — he took a 15-day DL stint in early July, came back too soon, and went back on the shelf for all of August. His first game back, on September 2, he allowed the first three batters he faced to reach and two of them to score, blowing a one-run lead. After that outing, he made nine more appearances, spanning 8.2 innings, in which he allowed one run, struck out 14 batters, and picked up a win and six saves.

As for the drop in velocity, he was pitching through a sore pitching elbow. Or maybe he’s just starting to get old, and he’ll have to live with pitching at 95 mph instead of 96 now. He’s got some room to play with, because — and this must’ve gotten lost along the way somehow — he’s been every bit as good as Chapman over the past three years, even with the bumpy road in 2016.

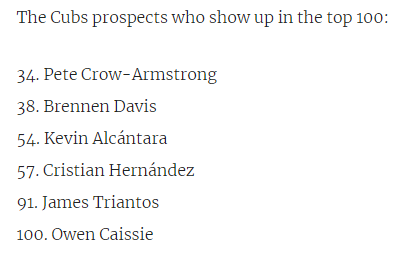

Since 2014, when Davis became a reliever full time, 92 pitchers have thrown 150 innings, with at least 80 percent of their appearances coming in relief. As relievers go, these guys are pretty good, because if you’re bad, you stop being a 50-inning-a-year reliever and become a high school gym teacher. Among these pitchers, Davis is eighth in K%, fourth in WPA (despite not becoming the Royals’ closer until late 2015), and first, by far, in ERA+ at 351. Zach Britton is the only other pitcher over 300, and Aroldis Chapman, Andrew Miller, Dellin Betances, Darren O’Day, and Mark Melancon are the only other pitchers with an ERA+ over 200 in that span. Meanwhile, Davis has appeared in 20 postseason games since 2014, striking out 38 against five walks, 14 hits, and a single earned run in 25 innings.

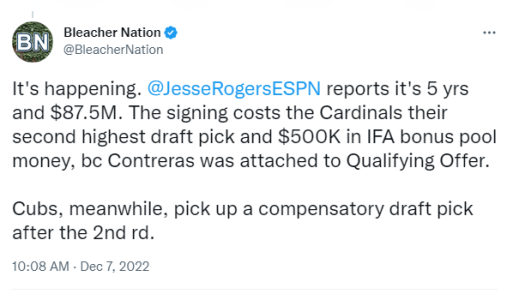

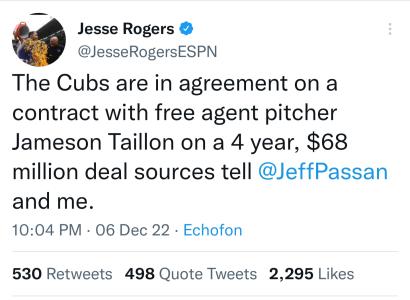

Melancon just signed a four-year, $62 million contract with the Giants, and Chapman and Miller commanded outrageous prospect packages at the deadline. Closers of this tier are simply not fungible like normal relievers, even good relievers. Worry about Davis’s forearm strain if you like, or the ongoing march of time, or his salary, but there is no empirical argument that he’s not a Chapman- or Miller-level pitcher.

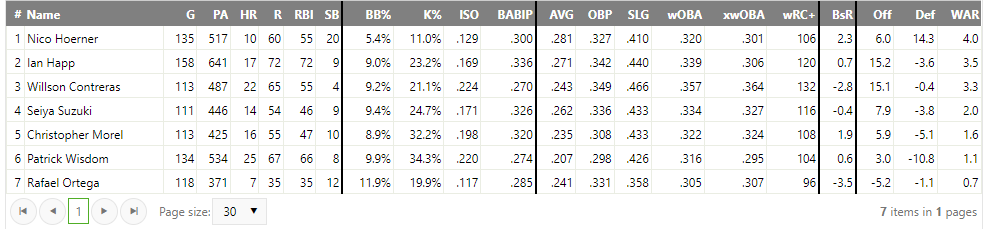

Soler, meanwhile, has hit .258/.328/.434 over 765 career plate appearances, which doesn’t look that bad — it’s a 107 OPS+, after all — but the deeper you dig into Soler’s stats, the worse he looks. Since 2014, 374 players have registered 500 or more plate appearances. Among those, Soler has the 38th-highest strikeout rate and the 31st-highest swing-and-miss rate. That’s not awful on its own — Javier Báez and Kris Bryant both swing and miss more — but Bryant, in addition to being a third baseman, has the 14th-best wRC+ in baseball in that span, while Soler’s wRC+ ranks 135th. And while Báez is an elite defensive infielder, Soler, meanwhile, is a pretty bad defensive corner outfielder. You can’t find very many league-average hitters who can play defense like Báez, but league-average hitters who can defend like Soler are all over the place. And big 24-year-olds who can’t hold down a corner outfield spot tend to turn into first basemen and designated hitters pretty quickly.

Since 2000, 80 corner outfielders aged 25 or younger have amassed 500 plate appearances through their first three seasons. Soler is tied for 37th in OPS+, with Wil Myers and Travis Buck, if you needed a clear indicator of the two paths his career could take. And that’s just factoring in Soler’s bat, which is his primary asset as a player. If you sort by WAR, he’s tied for 59th with Dayan Viciedo. Take out a 97-plate-appearance cameo in 2014, in which Soler slugged .573 while not playing enough defense to do any damage, and he’s been about replacement-level over the past two seasons. As a fourth outfielder and a scary guy to bring off the bench with men on, Soler’s just fine, but he’s had two and a half years to prove he’s the impact hitter the Cubs paid for, and he’s been outhit by Yangervis Solarte.

And if we’re buying canned goods because Davis went on the DL last summer, Soler has missed time for hamstring and ankle injuries in each of the past three seasons.

It’s tough to even make a case for this as a straight salary dump, because while Davis is due $10 million this year, that’s not a ton of money to a team like Chicago. Soler makes less per year, but he has about $17.7 million left on his deal over the next four years. Let’s say Davis blows out in spring training and misses the whole year, while Soler either gets hurt again or continues to be a below-average player; the Royals are now on the hook for 77 percent more money than they were before.

But what if Soler gets healthy and figures it all out? At age 25, and in his third full big league season, I wouldn’t put money on it, but it’s certainly possible. After this season, Soler can opt out of his annual salary of $4.67 million and enter arbitration with three-plus years of service time, which he’ll do only if he becomes that 30-home-run bat the Royals clearly think he can be.

In that case, we might look to Oakland’s Khris Davis, who hit 42 home runs for the A’s this past season and whom MLB Trade Rumors projects to make $5 million in arbitration on three-plus years of service time. After that, Soler’s only going to get more expensive if he’s good — still not market value, because arbitration is a scam run on young big leaguers — although not the bargain-basement deal his lower salary suggests right now. But if Soler continues to be the player he has been, he’s going to eat up $4.67 million a year no matter what.

For this to look even remotely good for Kansas City, one of two things needs to happen: Davis needs to get hurt and/or catastrophically old this season, or Soler needs to flip a switch and discover something in his game that hasn’t been in evidence for two years. I don’t think either one’s likely enough to hit the go button on this trade. Soler is talented, and relatively young, but given what pitchers of Davis’s quality have cost recently, it’s hard to believe the Royals couldn’t have done better.

@ Dex

@ Dex