Still going through this as it's pretty lengthy but it's well worth a read. I have several years of experience doing business, mostly as a seller, on such a social media black market so I will try to expand on the article tomorrow (it's kinda late at this moment) with some of my personal experiences and knowledge on the topic I've gained through the years. Bots are admittedly not my specialty but they are sold on the same marketplace I frequent, just in a different category of goods. So I can have a look around at the kind of bots being sold, their going rates, ...

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/01/27/technology/social-media-bots.html

The Follower Factory

Everyone wants to be popular online.

Some even pay for it.

Inside social media’s black market.

Paragraphs from the article that I can expand on with my own experiences or findings will be put in quotes so it's easier to distinguish my writings from that of the article.

The first few paragraphs are about a specific high level company that deals in social media bots, Devumi, so there's not much I can add to that.

Kristin Binns, a Twitter spokeswoman, said the company did not typically suspend users suspected of buying bots, in part because it is difficult for the business to know who is responsible for any given purchase. Twitter would not say whether a sample of fake accounts provided by The Times — each based on a real user — violated the company’s policies against impersonation.

“We continue to fight hard to tackle any malicious automation on our platform as well as false or spam accounts,” Ms. Binns said.

Unlike some social media companies, Twitter does not require accounts to be associated with a real person. It also permits more automated access to its platform than other companies, making it easier to set up and control large numbers of accounts.

They actually do suspend users fairly regularly for using bots, however there is no automated system or set requirement to

suspend them that I am aware of. They do have a system that flags suspicious activity but their security staff has to manually act on it. It's pretty rare for them to suspend influential accounts even with very obvious bot usage. Celebrities for example have virtually nothing to worry about. Others such as those who are in early stages of trying to grow a page and decide to make use of bots, even in numbers of just a few thousand, will set off far more red flags and it's not uncommon for those kind of cases to be suspended. Spreading out your bot usage over an extended period rather than an immediate boost will decrease that risk.

They also suspend the bots themselves, this is evidenced by the various qualities of bots on the market. Generally the lower the price, the higher the % of bots that will get suspended down the line. I've tested it before. I knew someone who was handing out free 1000 twitter follow bots in order to promote a service so I made use of it to give some followers to anyone who asked. It was practically instant delivery but it was pretty obvious that the followers were bots. Within a week the number of followers had already dropped by several hundred due to suspensions.

Also, when you are suspended by Twitter there is little to no chance of ever getting unbanned, unlike Instagram where it'll only cost you about $200 to unban your account. Twitter is very strict when it comes to that.

Instagram is the polar opposite. They do enforce obvious bot usage even against accounts with hundreds of thousands or even over 1 million of real followers but you can just pay for an unban service most of the time so there's not much point to it.

Their price also depends on the kind of functions they perform. Speaks for itself but bots that can retweet, tweet, push hashtags or even DM are going to be more expensive than bots that can only perform a single function such as following.

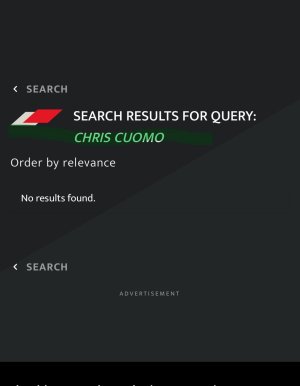

As you can see in this image, this is a vendor who offers a panel-based service with a large network of bots on all the primary social media platforms, including Soundcloud and Youtube. The ad is large so I couldn't fit them in all in the image. This particular service starts at $0.05 per bot at the lowest tier. For Twitter they offer followers, re-tweets and likes. By using a panel format, the user can easily direct bots on various platforms to do their bidding through an instant auto-buy system. Hence why it is so popular. This service has thousands of clients for example.

Here's an example of what you may come across on the kind of social media black market the NYT piece refers to: (I edited specific names and services)

The Influence Economy

Last year, three billion people logged on to social media networks like Facebook, WhatsApp and China’s Sina Weibo. The world’s collective yearning for connection has not only reshaped the Fortune 500 and upended the advertising industry but also created a new status marker: the number of people who follow, like or “friend” you. For some entertainers and entrepreneurs, this virtual status is a real-world currency. Follower counts on social networks help determine who will hire them, how much they are paid for bookings or endorsements, even how potential customers evaluate their businesses or products.

High follower counts are also critical for so-called influencers, a budding market of amateur tastemakers and YouTube stars where advertisers now lavish billions of dollars a year on sponsorship deals. The more people influencers reach, the more money they make. According to data collected by Captiv8, a company that connects influencers to brands, an influencer with 100,000 followers might earn an average of $2,000 for a promotional tweet, while an influencer with a million followers might earn $20,000.

Genuine fame often translates into genuine social media influence, as fans follow and like their favorite movie stars, celebrity chefs and models. But shortcuts are also available: On sites like Social Envy and DIYLikes.com, it takes little more than a credit-card number to buy a huge following on almost any social media platform. Most of these sites offer what they describe as “active” or “organic” followers, never quite stating whether real people are behind them. Once purchased, the followers can be a powerful tool.

“You see a higher follower count, or a higher retweet count, and you assume this person is important, or this tweet was well received,” said Rand Fishkin, the founder of Moz, a company that makes search engine optimization software. “As a result, you might be more likely to amplify it, to share it or to follow that person.”

Twitter and Facebook can be similarly influenced. “Social platforms are trying to recommend stuff — and they say, ‘Is the stuff we are recommending popular?’” said Julian Tempelsman, the co-founder of Smyte, a security firm that helps companies combat online abuse, bots and fraud. “Follower counts are one of the factors social media platforms use.”

Like it or not but yes, "social media influencer" is an actual job. One that can potentially earn mass amounts of money.

I'm no influencer but what I do is very closely related. I have a more detailed summary regarding what exactly it is that I do here:

https://niketalk.com/threads/you-ca...t-using-instagram.669066/page-2#post-29419266

To briefly summarize, I acquire valuable social media usernames and sell them to private individuals or companies. Valuable usernames would be common nouns, animals, locations, sports, celebrities, athletes, first names, ... The more common and popular, the more expensive.

There are 2 reasons there is a market for this in the first place:

- Vanity/Status: This is the main factor. Many people desire a "cool username" on their favorite platform(s) and are willing to pay anywhere from $20 to $15000 for that purpose. The latter is an extreme outlier and that $5k-15k range is reserved almost exclusively for what they see as the ultimate status symbol, a 1 letter username such as A, B, ...

The overwhelming majority of sales for this purpose are probably around the $150-200 mark.

- Monetizing purposes: This is where the big money is involved. Usernames sold for this purpose are referred to as "niche" usernames. A good example would be something like "fitness", "nature", "fashion", ...

They are status symbols as well of course but their primary purpose is growing the usernames into successful pages in order to monetize them. A username like fitness or fashion is going to do a lot of work for you because simply the name itself already attracts tons of people even without any content on the page. So it's just a matter of providing content in a way that attracts more followers and more importantly holds on to them. The monitizing comes in through promotion, advertising, digital marketing (AdSense, ...) or even just paid shoutouts. All of these can bring in tons of money and while the NYT is definitely off the mark with saying that someone with 1m followers can get $20k for a promotion, that's certainly the kind of money you can bring home in a month with over 1m followers and maximizing your monetization.

A friend of mine for example owns a page with around 6.1m followers at the moment. Back when his page was at 2m followers he received a $40k offer to buy his account from a rich investor. He turned it down because he consistently makes a lot more than that over time. And it paid off because he's now swimming in money with 6m followers. I'm guessing the NYT was referring to

celebrities with 1m+ followers being paid up to $20k for a promotion. There's a difference there. In many cases these are just regular people like you or me.

This quote from the NYT piece is a pretty good example of the kind of money an influencer can bring in. Note how young these 2 are. Now think of the kind of money experienced adult individuals and companies, often with marketing degrees, can bring in.

Influencers need not be well known to rake in endorsement money. According to a

recent profile in the British tabloid The Sun, two young siblings, Arabella and Jaadin Daho, earn a combined $100,000 a year as influencers, working with brands such as Amazon, Disney, Louis Vuitton and Nintendo. Arabella, who is 14, tweets under the name Amazing Arabella.

What I described above is essentially the role of a "social media influencer" and while it sounds incredibly corny, you can take my word for it that these people can make boat loads of money. More often than not they also have multiple pages, not just one with tons of followers. Some do it all themselves while others subcontract content creators so they can manage a network of different highly popular pages at the same time.

Others also form a whole company based around it. There is one company in particular that possesses mass amounts of wealth through the accounts they own. They're called Guff and own dozens of instagram pages like Tech, Science, ... Some of them may be banned or lost their verification badge by now because the company has engaged and continues to engage in account buying. Though basically everybody does it, especially with that kind of money involved.

I've done business with and had negotiations with similar companies, though 99% of my business is with private individuals.

These fake accounts borrowed social identities from Twitter users in every American state and dozens of countries, from adults and minors alike, from highly active users and those who hadn’t logged in to their accounts for months or years.

Sam Dodd, a college student

and aspiring filmmaker, set up his Twitter account as a high school sophomore in Maryland. Before he even graduated, his Twitter details were copied onto a bot account.

The fake account remained dormant until last year, when it suddenly began retweeting Devumi customers continuously. This summer, the fake Mr. Dodd promoted various pornographic accounts, including Mr. Leal’s Immoral Productions, as well as a link to a gambling website.

“I don’t know why they’d take my identity — I’m a 20-year-old college student,” Mr. Dodd said. “I’m not well known.” But even unknown, Mr. Dodd’s social identity has value in the influence economy. At prices posted in December, Devumi was selling high-quality followers for under two cents each. Sold to about 2,000 customers — the rough number that many Devumi bot accounts follow — his social identity could bring Devumi around $30.

The stolen social identities of Twitter users like Mr. Dodd are critical to Devumi’s brand. The high-quality bots are usually delivered to customers first, followed by millions of cheaper, low-quality bots, like sawdust mixed in with grated Parmesan.

Some of Devumi’s high-quality bots, in effect, replace an idle Twitter account — belonging to someone who stopped using the service — with a fake one. Whitney Wolfe, an executive assistant who lives in Florida, opened a Twitter account in 2008, when she was a wedding planner. By the time she stopped using it regularly in 2014, a fake account copying her personal information had been created. In recent months, it has retweeted adult film actresses, several influencers and an escort turned memoirist.

“The content — pictures of women in thongs, pictures of women’s chests — it’s not anything I want to be represented with my faith, my name, where I live,” said Ms. Wolfe, who is active in her local Southern Baptist congregation.

Other victims were still active on Twitter when Devumi-sold bots began impersonating them. Salle Ingle, a 40-year-old engineer who lives in Colorado, said she worried that a potential employer would come across the fake version of her while vetting her social media accounts.

“I’ve been applying for new jobs, and I’m really grateful that no one saw this account and thought it was me,” Ms. Ingle said. Once contacted by The Times, Ms. Ingle reported the account to Twitter, which deactivated it.

This part provides some insight about the more high-quality bots. There is a bit of variance in the functions of these bots, how they operate and how they were obtained in the first place.

It's not that uncommon to see someone wanting to buy bulk loads of "aged accounts", usually on Twitter. The older an account is, the less likely it is seen as fake. Then it's just a matter of making them look somewhat real. In more advanced cases this can mean actively impersonating someone's identity. Another method is also to buy bulk loads of stolen accounts, inactive ones of course. It's a lot harder to jack a twitter account nowadays than it was 5 years ago so those kind of bulk purchases are rare but also most effective since they are real people's accounts. The cheap bots with a very obvious fake look to them are generally just created through an automated mass-registration program. Very little effort required but they're also the absolute bottom tier.

Some bot users also offer payments for people to help cultivate their bot networks. Here's a fairly recent "job offer" I came across for example.

The NYT article also talks about the latter:

Mr. Calas’s lawsuit also revealed something else: Devumi doesn’t appear to make its own bots. Instead, the company buys them wholesale — from a thriving global market of fake social media accounts

The Social Supply Chain

Scattered around the web is an array of obscure websites where anonymous bot makers around the world connect with retailers like Devumi. While individual customers can buy from some of these bare-boned sites — Peakerr, CheapPanel and YTbot, among others — they are less user-friendly. Some, for example, do not accept credit cards, only cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin.

But each site sells followers, likes and shares in bulk, for a variety of social media platforms and in different languages. The accounts they sell may change hands repeatedly. The same account may even be available from more than one seller.

Devumi, according to one former employee, sourced bots from different bot makers depending on price, quality and reliability. On Peakerr, for example, 1,000 high-quality, English-language bots with photos costs a little more than a dollar. Devumi charges $17 for the same quantity.

The price difference has allowed Mr. Calas to build a small fortune, according to company records. In just a few years, Devumi sold about 200 million Twitter followers to at least 39,000 customers, accounting for a third of more than $6 million in sales during that period.

Another noteworthy part is that Twitter's security, or lack thereof, actually plays into the hands of bot users and network owners. It really wouldn't be that hard to put even just a few safeguards in place that prevent programs like automated mass-registrations from working. This is how the vast majority of bots are created in the first place. They could simply filter out automated registrations by having various kinds of captcha codes, the typical "select all images with traffic signs" kind of safeguard, ... during the registration process. It is by no means hard and you can draw your own conclusions about Twitter's stance on bots given the utter disregard for basic anti-spam safeguards.

Yet Twitter has not imposed seemingly simple safeguards that would help throttle bot manufacturers, such as requiring anyone signing up for a new account to pass an anti-spam test, as many commercial sites do. As a result, Twitter now hosts vast swaths of unused accounts, including what are probably dormant accounts controlled by bot makers.

Former employees said the company’s security team for many years was more focused on abuse by real users, including racist and sexist content and orchestrated harassment campaigns. Only recently, they said, after revelations that Russia-aligned hackers had deployed networks of Twitter bots to spread divisive content and junk news, has Twitter turned more attention to weeding out fake accounts.