Clippers, Warriors biggest foes aren’t on court, it’s the new CBA

Is this the end of an era?

Not the era you were thinking of, the one that began with the Golden State Warriors storming to the championship in 2015 and then winning four rings in eight years. No, I’m talking about a related but more recent era: the one where late-stage contenders keep themselves in the chase by shooting money out of a firehose.

The two leading adherents of that strategy, the Warriors and LA Clippers, both find themselves on thin playoff ice at the beginning of the week. It’s just the first round and each team had hopes for a much grander and longer playoff journey, but the Warriors are in a dogfight with Sacramento, tied 2-2 without home-court advantage, and the Clippers are on the brink of elimination against Phoenix, down 3-1.

If those two teams go down, headed to the bottom of the sea with them might be an entire model of how teams have been assembled in recent years.

That’s not just because the 2022-23 versions of the Warriors and Clippers are both incredibly expensive without being notably dominant; each will fork over a nine-digit luxury tax check to the league above and beyond what they pay in salary. Golden State’s tax penalty will be more than Sacramento’s payroll; you’d think with such a difference the series wouldn’t be so even.

Yet the money is barely the problem; the owners of these two teams have been unbothered by massive payrolls and cutting huge tax checks. Instead, it’s the roster-building rules that accompany such spending that will make life untenable for the NBA’s free spenders. Provisions of the new collective bargaining agreement (CBA) between the league and the Players’ Association that will take effect on July 1 make it prohibitively difficult to successfully operate a team this way.

The Athletic recently reviewed a copy of the term sheet of the new CBA, and spoke to multiple agents and executives about the league’s proposed changes.

The most notable change is that the new CBA contains a “second apron” set at $17.5 million above the luxury tax (with increases in future years commensurate with any salary cap rise) that places severe restrictions on any team that exceeds it. It also has harsher penalties even for teams that exceed the first apron that has already been in place at $7 million over the tax line, and comparatively lighter financial restrictions than currently in place for teams that merely exceed that tax line up until the apron.

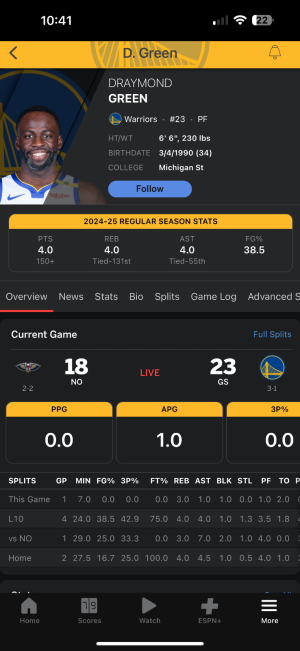

The Clippers and Warriors, I’ll remind, you are both about $40 million above that line this season. More problematically, they are both locked into payrolls that soar just as high above the tax line for 2023-24. The Clippers, in fact, project to be the first team in in NBA history with a payroll above $200 million, while the Warriors could blow well past even that figure if Draymond Green doesn’t leave in free agency. Even in the years beyond, it will be difficult for either to lower payroll much without substantially degrading the roster.

The league is phasing in the new second apron over just a two-year period, according to league sources who were granted anonymity so they could speak freely, and many of the changes will hit sooner. As a result, both teams will have a difficult time just maintaining what they already have, and extremely limited ability to add any worthwhile pieces.

The result, multiple league sources say, is a tax regime so draconian that even these free-spending clubs may choose not to swim in the deep end. The likely end-game by mid-decade is what might be described as a “soft hard cap” — one that can be exceeded, perhaps, in some situations, but in reality will be so limiting for most teams, at most times, that they will rarely if ever go beyond it.

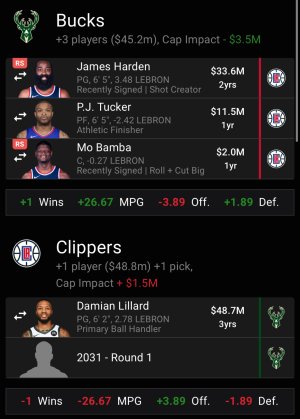

I should note that, technically, a few other teams could be impacted by these rules. The Bucks, Celtics, Mavericks, Lakers and Suns also are over the $17.5 million line this season, for instance. However, each of those are partly the result of smaller decisions that easily could have been modified to accommodate the new rules regime. Of those teams, only the Bucks and Suns face any strong possibility of issues with respect to that line for next season. Even then, each could relatively easily sidestep the limitations of the higher apron by trading a secondary role player (e.g. Pat Connaughton or Landry Shamet).

The Clippers and Warriors, on the other hand, are in deep enough that significant, gutting adjustments would have to be made to get below the second apron. And in the future, willingness to pay might not even be a factor: The rules are draconian enough that it’s extremely difficult to even reach the point of being $40 million over the tax, much less win once a team’s payroll reaches that point.

The choices are more difficult for both, of course, given their present state of affairs: still good enough to win on the right day, but with key players in their 30s, little high-end talent in the developmental pipeline, and shorn of draft picks and cap flexibility. Even in a down year in the West, they finished fifth and sixth this year, respectively.

Can they even tread water in those spots going forward? As additional details about the new agreement have leaked out, it’s become clear just how harshly the new agreement will treat the highest-spending teams. The specific ways that it penalizes teams that are exceeding the penalty are myriad. Most of these have already been reported here (thanks, Shams!) or in other outlets, but to review:

- Teams above the second apron will have no midlevel exception, not even the taxpayer MLE of yore. They also may not use cash in trades, cannot trade for more money than is sent out, will pay tax at a higher rate and have a higher repeater penalty.

Finally, they may not aggregate contracts in trades. That aggregation rule is key, and not just for the Clippers and Warriors. Consider, for instance, that the Kevin Durant and Kyrie Irving trades to Phoenix and Dallas, respectively, would have been virtually impossible with those rules … especially since Brooklyn was deep in the tax and was also blocked by the same rules.

- One new penalty that generated huge criticism was the “jailing” for future draft picks for teams that exceed the second apron. Those teams will not be able to trade a first-round pick seven years in the future, limiting the haul available for Durant-style blockbusters. More importantly, perhaps, if those teams stay above the tax apron in more than one of the next four years, the pick gets pushed to the end of the first round in the year in question … regardless of where the team might finish.

- That last detail is another key one. Teams this expensive usually get that way as part of a damn-the-torpedoes, chips-in mentality that robs from the future to pay the present. Implicit in that bargain is the notion that the team of the future will likely need to tank its way to high draft picks to replenish the roster.

If the future draft pick gets kicked back to the end of the first round, the tank scenario is off the table in that far-off season … perhaps taking some of the “win now” incentive to rob from the future along with it. This potential penalty is one of the bigger reasons we could see the second apron operate as a de facto hard cap that is only exceeded occasionally … a maximum of twice every five years, to be particular.

- The restriction on signing buyout players who had made more than the MLE also seemed slightly ridiculous to most insiders; these players rarely end up mattering. However, it would invalidate a couple of scenarios that happened this year, such as the Clippers’ acquisition of Russell Westbrook or the Suns’ addition of Terrence Ross.

- Not only can teams not aggregate in trades to take on more salary, but also, league sources say, the new agreement appears to disallow teams to “aggregate down.” In other words, a team couldn’t trade two players who make $20 million each for one who makes $30 million and one who makes the minimum, even though the net effect would be to lower payroll for a high-spending team.

- While the harshest penalties are reserved for those who exceed the second apron, the NBA’s fangs also came out a bit for teams above the first apron at $7 million above the tax. Those teams will have a more limited taxpayer MLE ($5 million, two-year maximum) than in the past agreement, will have a 100 percent multiplier for trade salaries (in other words, can’t take back more than they send out), and will face the same buyout restrictions as the second apron teams. These rules would have prevented Denver from signing Reggie Jackson, for instance, and stopped the Lakers from acquiring Rui Hachimura.

Additional details in the agreement, meanwhile, make life slightly easier for everyone operating below the tax apron. It will likely have the net effect of increasing the number of teams that go a few million into the tax, rather than slamming the brakes right at the tax line:

- Let’s start with the financial part. One penalty for going over the luxury tax line was missing out on a giant luxury tax distribution check, courtesy of profligate spenders like the Clippers and Warriors. The 21 teams below the tax line this year can expect a $12.5 million windfall just by being below the line, because the Warriors and Clippers alone are paying over $300 million into the system. Keeping their tax overages smaller likely reduces that payout. With that carrot reduced, more teams might be open to exceeding the tax by a few million.

- Additionally, while tax penalties will increase for the Clippers and Warriors of the world, the lowest two brackets of tax will actually decrease under the new CBA. Those correspond to teams currently $10 million or less above the tax line; they’ll owe $1 for every dollar over in the lower bracket (zero to $5 million currently), down from the present $1.50; and $1.25 in the second-lowest bracket ($5 million tot $10 million currently) down from the present $1.75.

- Whether this is good for small-market teams in the aggregate has been a topic of some debate. Giant tax checks can and do take some small-market teams from red to black. On the other hand, those teams have a much better chance of competing at the highest levels if their overall spend is more comparable.

- The new rules also make it harder for a Donald Sterling-type cheapskate owner to just sponge off the taxpaying teams, especially with a requirement that teams spend at least to the cap floor in the offseason if they want to receive a luxury tax distribution.

The devil is in the details on something like this, of course, and we’ve yet to see the legalese fine print (and, thus, teams have yet to figure out the most creative ways to circumvent it). However, league sources say there will be that two-year phase-in of the restrictive treatment of the league’s profligate spenders, giving teams like the Clippers and Warriors a very limited window to get their books in order.

Additionally, one can already look at certain situations with these teams and see how either A) they might not have ever come to pass in the next CBA or B) how much harder they will be to continue.

Take the Clippers, for instance, and Westbrook. He would not be a Clipper right now under the new CBA because the Clippers would not have been permitted to sign him after his buyout, given that Westbrook made more than the MLE last year. He also would not have been traded from the Lakers in the first place, given that the Lakers were already over the first apron and added about $5 million in salary in that deal.

And signing him for the future? With no taxpayer exception and no Bird rights, the Clippers would be limited to offering him a minimum contract, despite his being the best Clipper on the floor in their last two playoff games.

Similarly, the Clippers would not have been able to aggregate Luke Kennard and John Wall in a deadline-day trade for Eric Gordon … or for that matter, to sign Wall in the first place with their taxpayer midlevel exception. Even decisions that would have been expensive but no-brainers for the Clips in the past and remain allowable under the new CBA — such as re-signing Mason Plumlee with his Bird Rights this coming summer — now carry much deeper implications for roster building.

As for the Warriors, they would have been unable to sign Donte DiVincenzo this past summer with their taxpayer midlevel exception; nor could they have used cash to move up in the draft and select Ryan Rollins.

Going forward, the new CBA exacerbates the Warriors’ already existing payroll question. Re-signing or extending Green and Klay Thompson would likely make the Warriors’ overall roster even more expensive relative to the tax in 2024-25 than it is today. However, they would be unable to fill out the roster with the DiVincenzos and Otto Porters of the past via the MLE, could not aggregate their smaller contracts in trades, and could not use cash to buy their way into the second round of the draft.

The irony, of course, is that the catalyst for much of his was likely the massive payroll of last year’s championship Warriors. … who could have had the same core regardless, and spent nearly as much, even with the new rules in place. They were under the apron in 2019-20 when they acquired Andrew Wiggins, and only went over in 2020-21 to add minimum contracts and re-sign their own players and draft picks. The Porter free agent signing in 2021 is the only one that would have changed under the updated CBA; Porter was a useful component of the 2022 champions, but hardly the catalyst.

Nonetheless, one of the big micro-battles of the new CBA was the balance of power between high-spending teams and their smaller-market brethren. The latter group won this round, emphatically.

The new rules not only clip the wings of the league’s most profligate spenders in general, but also catch the Clippers and Warriors in particular at a time when they are already facing something of a crossroads for their current builds. As much as these teams are facing battles on the court this week, their biggest challenges may yet come off the floor this summer.

I could stay up for the other west series with relative ease.

I could stay up for the other west series with relative ease.