‘Top Chef’ Alum Tu David Phu Wants to Know Why You Don’t Want to Pay $10 for Banh Mi

9

The Vietnamese-American chef’s new Oakland pop-up is the latest battleground in an age-old debate

by

Luke Tsai Oct 14, 2019, 3:14pm PDT

When

Tu David Phu started making plans for

BanhMi-Ni, his new lunchtime Vietnamese sandwich pop-up in Oakland, one of his motivations was that he wanted to make food that would be more accessible to everyday working-class people. Perhaps most famous for his

2017 stint on Top Chef, Phu was last seen selling $32 bowls of Vietnamese-inflected bouillabaisse

at the Tenderloin supper club Black Cat; before that, he did a series of

Vietnamese-inspired tasting menu pop-ups that charged as much as $90 a head.

In comparison, selling $10 sandwiches from a window inside of Uptown Oakland’s

Copper Spoon seemed like a no-brainer, from an affordability standpoint.

Imagine the chef’s surprise, then, when many of the initial responses to BanhMi-Ni, which opened two weeks ago, were from customers and would-be customers who found $10 to be an outrageous price point for banh mi — especially from a restaurant that was claiming affordability as one of its main virtues. “I’m down to try,” one online commenter wrote, “but ‘affordable meals’ and ‘$10 banh mi’ seems contradictory.”

Naturally, Phu took to Twitter to clap back.

RELATED

Opinion: Yelp Reviewers’ Authenticity Fetish Is White Supremacy in Action

In a tweet last Thursday, Phu argued that some of the banh mi shops that charge $3 or $4 a banh mi are only able to do so because they’re locked into leases at below-market rates. More to the point, he added, “Why aren’t you comparing me to the $15 burgers and $25 lunches in nearby Oakland spaces? Is it because we are serving POC food?”

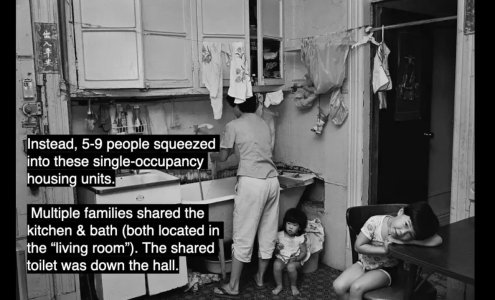

Banh mi, of course, has a long history as a working-class food staple in America’s Vietnamese enclaves, so it isn’t entirely surprising that some customers — particularly Vietnamese Americans who grew up on $3 banh mi — might take issue with a celebrity chef selling a gussied-up version for three times the price.

But Phu believes there’s a kind of racism at play in the belief many Americans have that certain kinds of food should always be cheap — often the ones associated with non-European immigrant communities. Here in the Bay Area, prominent local chefs like Richie Nakano (formerly of Hapa Ramen) and Preeti Mistry (of the now-closed Juhu Beach Club) have

argued,

again and again, that it is nonsensical, and often flat-out racist, to say, for instance, that it’s okay to charge $25 for a plate of pasta at a nice Italian restaurant, but that a bowl of ramen — which might take even more time and labor to make — should never cost more than $12.

“[There’s not much] difference between dim-sum dumpling making and a three-Michelin-star Italian [restaurant] making agnolotti,” says Phu, who has practiced both categories of pasta-making in his career. “It’s just as hard.”

The same goes for the sandwiches at BanhMi-Ni, which Phu says he makes with high-quality ingredients while also wanting to pay his staff a living wage. At the end of the day, he believes what he’s offering is a good deal: $12 for a full meal that comes with a bottle of water and a bag of chips. (See the full menu below.) “Compare me to all the other lunch options,” he says.

Pork chashu banh mi Phi Tran

What Phu doesn’t want to get caught up in is arguments about authenticity. “Banh mi is a third-culture product,” he says, pointing out the history of French colonialism baked into the very origins of the sandwich. “I don’t think there are any rules and regulations regarding banh mi.”

For Phu, the essence of banh mi can be stripped down to three core ingredients: pickled carrots, pickled daikon, and pâté. All of the sandwiches at BanhMi-Ni — except the vegan option — have those elements, but beyond that it’s pretty much anything goes. There’s one version that Phu makes with spicy pastrami that is a tacit nod to the

time he spent working at Saul’s Delicatessen; in another, he gives pork loin the kind of slow-poach treatment you’d typically associate with Japanese-style chashu.

Most controversial is probably Phu’s decision to eschew the traditional crisp baguette in favor of a soft Mexican torta roll, which he then toasts on a panini press — hence the name, “BanhMi-Ni” — so that the outside still takes on a little bit of crunch. “Give me hell or high water, I liked Wonder Bread [growing up]. I like soft bread,” he says.

Phu says he’ll steer the traditionalists who expect the hit of Maggi seasoning (and MSG) you get at old-school banh mi spots toward his chashu banh mi — which, to be clear, doesn’t actually include Maggi seasoning. As for the customer who comes to BanhMi-Ni craving a classic banh mi dac biet — the one with the cold cuts, often “No. 1” at the top of the picture menu?

“I would just tell them, ‘This isn’t the place for you,’” Phu says.

Instead, Phu says he’s happy to champion the matriarchs who are typically the ones running the Bay Area’s more traditional banh mi shops. “They can do that [type of banh mi] way better than I can,” he says.

At the same time, the chef believes that customers need to reexamine their assumptions on pricing if they want their favorite old-school pho shops and banh mi joints to stay in business for the long haul.

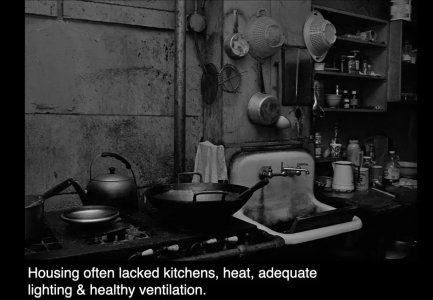

“All the Chinatowns and all the little communities of nostalgic feel that everyone loves — all of those are

going extinct right now,” Phu says. “It’s a fact: If people don’t adjust the way they think, if they’re not willing to change their perspective on what they expect from those food community spaces, those spaces are going extinct.”