Dr. Roberts and Dr. Kytle are the authors of

“Denmark Vesey’s Garden: Slavery and Memory in the Cradle of the Confederacy.”

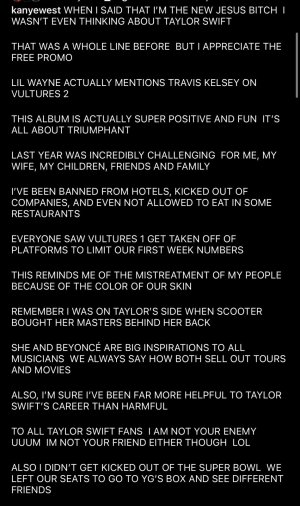

A video of the rapper Kanye West discussing slavery is a sad reminder of America’s historical amnesia about the brutal realities of that institution. “When you hear about slavery for 400 years,” he said in the clip, which was widely circulated on Twitter, “that sounds like a choice.”

Mr. West seemed to suggest that enslaved African-Americans were so content that they did not actively resist their bondage, and, as a result, they bear some responsibility for centuries of persecution.

He’s not alone in his thinking. In 2016, the former Fox News host Bill O’Reilly asserted that slaves were “well fed and had decent lodgings.” Last September, the Alabama senatorial candidate Roy Moore deemed the antebellum era the last great period in American history. “I think it was great at the time when families were united,” he declared. “Even though we had slavery, they cared for one another.”

Modern scholarship has debunked such whitewashing, accurately depicting slavery as an inhumane institution rooted in greed and the violent subjugation of millions of African-Americans.

Yet countless Americans have not learned these lessons. They cling, instead, to a romanticized interpretation of slavery, one indebted to a book published 100 years ago.

In the spring of 1918, the historian Ulrich Bonnell Phillips published his seminal study, “American Negro Slavery,” which framed the institution as a benevolent labor agreement between indulgent masters and happy slaves. No other book, no monument, no movie — save, perhaps, for “Gone With the Wind,” itself beholden to Phillips’s work — has been more influential in shaping how many Americans have viewed slavery.

An enslaved man tied to a whipping post, circa 1865.

An enslaved man tied to a whipping post, circa 1865.

Born in 1877 into a Georgia family with planter roots, Phillips developed an abiding sympathy for the Old South. He studied history at the University of Georgia and then as a graduate student at Columbia University under the tutelage of William A. Dunning, a scholar with a pro-Southern bent.

After earning his doctorate in 1902, Phillips set out to correct the slanted picture of the Southern past that he believed prevailed at the time. “The history of the United States has been written by Boston and largely been written wrong,” he lamented. “It must be written anew before it reaches its final form of truth, and for that work, the South must do its part.”

Phillips certainly did his. During his 30-year career, he published nine books and close to 60 articles, earning a series of prestigious professorships that culminated in a “very flossy job,” as he put it, at Yale University. This 1930 appointment reflected his stature as the country’s leading historian of slavery and the South, as well as the influence of his most important book, “American Negro Slavery.”

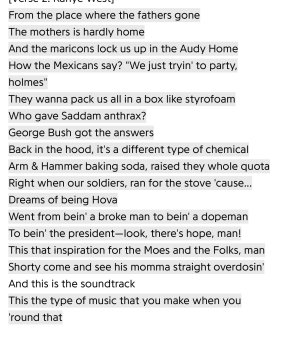

He was a prodigious, albeit selective researcher. Phillips found evidence in plantation records and Southern travelogues that bolstered the book’s benign interpretation of slavery, while downplaying evidence that did not. In his hands, plantations became idyllic sites where white families had modeled the habits of civilized life for their childlike black charges. “The plantations,” Phillips wrote, “were the best schools yet invented for the mass training of that sort of inert and backward people which the bulk of the American negroes represented.”

According to Phillips, slaveholders provided the enslaved with comfortable living quarters and plentiful rations and eschewed physical discipline. They rarely sold slaves, especially if it meant breaking up families. Slave owners’ rule “was benevolent in intent” and “beneficial in effect.”

Phillips’s use of the passive voice — “in March the corn fields were commonly planted” — further distanced the reader from slaves’ coerced labor. Enslaved African-Americans, in turn, displayed gratitude and loyalty to their masters. Phillips concluded that, while slavery may have been economically inefficient, “the relations on both sides were felt to be based on pleasurable responsibility.”

“American Negro Slavery” won widespread acclaim in the North and the South. Reviewers praised Phillips for his thorough research, charming style and lack of bias. In the words of the historian John David Smith, an expert on Phillips, the book served as “the definitive account of the peculiar institution” from World War I into the 1950s.

The book set the tone for the treatment of slavery in classrooms and textbooks across the country. “There was much to be said for slavery as a transition status between barbarism and civilization,” maintained a 1930 best seller, echoing Phillips almost verbatim. “The majority of slaves were … apparently happy.”

From the beginning, however, Phillips had his critics, who insisted on telling a more truthful, unvarnished history of slavery. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote a scathing review of “American Negro Slavery,” observing, “It is a defense of American slavery, a defense of an institution which was at best a mistake and at worst a crime.” Drawing on interviews with ex-slaves, sources Phillips rejected, the historian Frederic Bancroft published a 1931 book that exploded Phillips’s misrepresentations of the domestic slave trade.

Phillips’s critics grew more vocal in the 1950s and 1960s, as a new generation of scholars challenged his benign reading of slavery and the racism that stained almost every page of “American Negro Slavery.”

Yet while Phillips’s most egregious claims fell out of favor, the legacy of “American Negro Slavery” has proved tenacious.

According to a new Southern Poverty Law Center report on how slavery is taught in public schools, current pedagogy continues to focus on slavery from the perspective of whites, not the enslaved, while failing to connect the institution to the white supremacist beliefs that supported it. Textbooks often ignore slaveholders’ desire to make money and too easily slip into grammatical constructions — Africans “were brought” to America — that absolve enslavers of their actions.

Last year, a Charlotte, N.C., teacher asked her middle-school students to list “four reasons why Africans made good slaves.” An eighth-grade teacher in San Antonio recently sent students home with a work sheet titled “The Life of Slaves: A Balanced View.” It prompted students to list the “positive” aspects of slavery along with the “negative.”

We must confront mischaracterizations of the nature of slavery, whether nurtured in the classroom or broadcast on Twitter. After all, historical accuracy on this topic is not just about getting the past right; it is also about understanding the challenges of the present.

The persistence of racial inequality in America — from police brutality and school segregation to mass incarceration and wealth disparities — reflects, to some degree, the persistence of the Phillipsian take on slavery. If the institution were little more than a finishing school for African-Americans, then why acknowledge or address its pernicious legacies today?

.

.