After the Dallas Cowboys clinched the NFC East crown with a dominating 42-7 victory over the Indianapolis Colts Sunday, there was plenty of talk that Tony Romo, a quarterback by turns revered and maligned over his career in Dallas, should be a frontrunner for the NFL’s most valuable player award this season.

“He is certainly [the MVP] in my book,” Cowboys owner Jerry Jones told reporters Sunday.

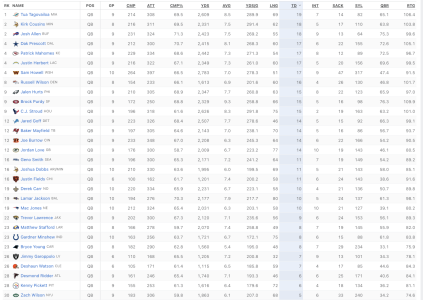

That Romo’s candidacy would even be a valid topic of conversation seemed unlikely before the season. He was coming off the worst two seasons of his career and turned 34 in April (statistical declines tend to hasten in a quarterback’s mid-30s). And yet, Romo has rebounded this year to post the best completion percentage, touchdown percentage, yards per attempt and passer rating in the NFL.

Since the passing game really started to take off in the late 1990s, the MVP has gone to a quarterback about three-quarters of the time (and six times in the last seven seasons). That’s justifiable given the position’s importance in the modern game (sorry, J.J. Watt), and Romo has been the league’s top QB this season by conventional measures.

But we can dig deeper into Romo’s statistical resume to see if he’s truly deserving.

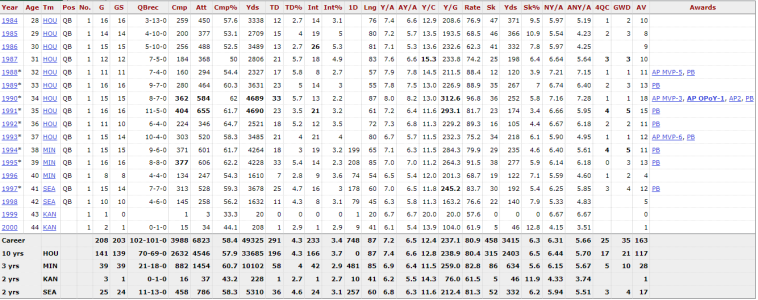

According to adjusted net yards per attempt (ANY/A), which tries to synthesize conventional stats (including sacks) in a more rigorous way than the NFL’s outmoded passer rating formula, Green Bay’s Aaron Rodgers has easily been the most effective passer in football this year (Romo is third behind Rodgers and football god Peyton Manning). As far as team stats go, ANY/A is a pretty reliable indicator of how efficient a passing offense has performed. Although it uses the same batch of QB stats the NFL’s been tracking since the late 1960s, ANY/A corresponds extremely well to team scoring (it has a correlation of 0.85 with points per game this season) and tracks even better (correlation: 0.89) with expected points, which attempts to filter out the effects of defense, special teams and field position on an offense’s scoring output.

The close correlation between ANY/A and team scoring explains why Romo’s Cowboys also trail Rodgers’s Packers in points per game, points per drive and expected points. And while some of those offensive differences may also be explained by disparities in rushing quality, Dallas’s running game has actually had a higher success rate — that is, the share of running plays that generate positive expected points — than Green Bay’s. As coaches intuited long ago, a running game’s most important characteristic is its consistency, both in putting the offense in more favorable down-and-distance situations and in chewing up the clock late in games. That’s why a rushing attack’s success rate correlates better with overall team offense than the number of yards or expected points generated on runs (either in total or on a per-play basis).

So it’s fair to say the Cowboys’ offense performed worse than the Packers’ despite the Cowboys’ running game providing more production behind Romo than Green Bay’s did for Rodgers. Plus, the Packers’ offense has produced better numbers despite facing tougher defenses. Green Bay has faced the league’s 14th-easiest slate of opposing defenses this season, according to the strength-of-schedule component of Pro Football Reference’s Simple Rating System. But the Cowboys have faced the fourth-easiest. PFR’s numbers imply that an average team would score about 0.9 more points per game against Dallas’s schedule than against Green Bay’s (yet the Packers have outscored Dallas by 2.2 PPG).

We can further unpack the Romo-versus-Rodgers debate by looking at play-by-play grading services such as Pro Football Focus (PFF). PFF grades Rodgers as the best quarterback in football so far this season by a comfortable margin, over No. 2 Drew Brees (Romo ranks sixth). PFF also grades Dallas’s offense as providing more support in the running game, both among its ball-carriers and its run-blockers (and this is without accounting for the fact that Rodgers himself graded better as a rushing QB than Romo). And since PFF attempts to hand out credit to receivers on passing plays independent of the quarterback himself, we also have evidence that Romo’s targets contributed more in the passing game (a cumulative +22.1 in PFF’s grading parlance) than Rodgers’s did (+12.6), despite Rodgers dropping back to pass nearly 100 more times than Romo.

The only real factors that might mitigate a landslide Rodgers MVP victory over Romo, then, are in the benefits each QB received from his pass protection and differences in — gulp! — clutch play. According to PFF, the Packers are by far the best pass-blocking team in the NFL; Romo’s Cowboys rank third, but have provided nowhere near the safety offered by Green Bay’s blockers. How much of an edge is this for Rodgers, though? A regression says that each point of PFF’s pass-blocking score has been worth about 0.007 adjusted net yards per attempt this season; that means Green Bay’s 31.2-point pass-blocking advantage over Dallas has really only contributed to 0.21 of Rodgers’s 0.44-ANY/A advantage over Romo in the passing efficiency department.

The clutch question leads to a similar conclusion, with one caveat. There’s no question that Romo has performed better than Rodgers in high-leverage moments. Romo’s win probability added (WPA, or the amount by which his team’s win probability increased on plays in which he passed the ball) is about 0.4 wins higher than what we’d expect from his expected points added (EPA), meaning he produced a greater share of his EPA in moments that had more bearing on the final outcome of the game. Meanwhile, Rodgers’s WPA is 0.25 wins lower than we’d expect from his EPA. But even after acknowledging that difference, Rodgers still crushes Romo on WPA — the clutch difference took a 1.5-win Rodgers edge and shrunk it to 0.8 wins.

Romo has ramped up his play in Dallas’s crucial December games, completing 79.2 percent of his passes for 688 yards and a 10-0 touchdown-to-interception ratio, so surely he would receive a boost if we weighted his stats by the playoff implications of each game. But in the end, both Rodgers’s Packers and Romo’s Cowboys have clinched playoff spots — so all those presumed swings in playoff probability just led to the same place.

All of this is why it’s very difficult to argue that Romo (or anyone else, for that matter) deserves the MVP over Rodgers. Individual football stats are inherently suspect because parsing credit among 11 players with varying responsibilities is extraordinarily difficult. But to the extent that we have evidence about individual quarterbacking performances, all signs point to Rodgers being more valuable than Romo this season.